|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

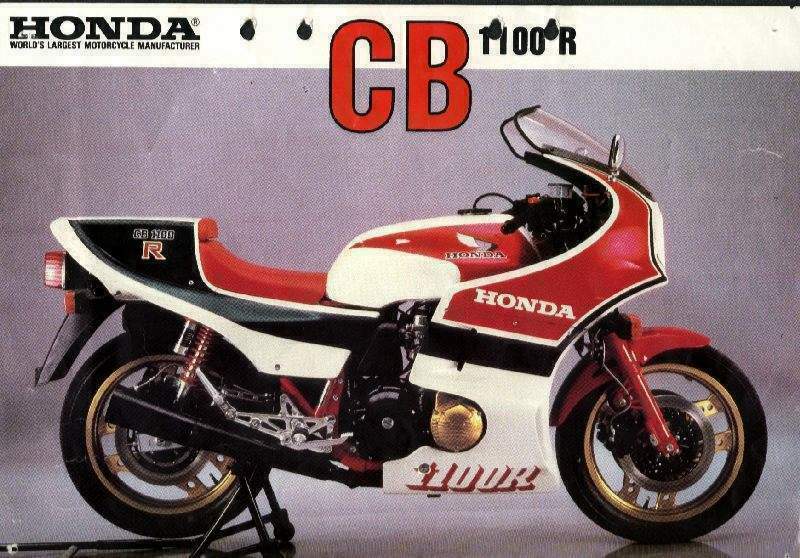

Honda CB 1100R BD |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Honda CB 1100R BD |

|

Year |

1983 |

| Production | 1500 units |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, transverse four cylinders, DOHC, 4 valve per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

1062 |

| Bore x Stroke | 70 x 69 mm |

| Cooling System | Air cooled |

| Compression Ratio | 10.0:1 |

|

Induction |

4x 33mm Keihin carbs |

|

Ignition |

Electronic |

| Starting | Electric |

|

Max Power |

120 hp / 87.5 kW @ 9000 rpm |

|

Max Power Rear Wheel |

106 hp @ 9000 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

98 Nm / 72.5 ft-lb @ 7500 rpm |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Final Drive | Chain |

| Frame | Steel tube double cradle |

| Front Suspension | Adjustable telescopic hydraulic fork |

| Rear Suspension | Swinging arm fork with adjustable Telehydraulic shocks absorbers |

| Front Brakes | 2x 296mm discs 2 piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | Single 296mm disc 2 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

100/90-18 |

|

Rear Tyre |

130/90-18 |

| Dimensions |

Width 805 mm / 31.7 in |

| Wheelbase | 1490 mm / 59 in |

| Seat Height | 795 mm / 31.3 in |

|

Dry Weight |

235 kg / 513.7 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

26 Litres / 6.9 gal |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

11.3 sec / 190 km/h |

|

Top Speed |

230 km/h / 143 mph |

|

Road Test |

| . |

The model designations are CB1100RB (1981), CB1100RC (1982), and CB1100RD (1983). The 1981 'RB' was half faired with a solo seat only. The 82 and 83 models have different bodywork including a full fairing, aluminium fuel tank, and pillion seat covered with a removable seat cowl. The 82 (RC) and 83 (RD) were largely similar in appearance, yet with considerable differences what concerns the full fairing and dashboard layout. None of the faring parts of any of the 3 models are interchangeable with one another. Other differences include the paint scheme, rear swing arm design and color and front fork design.

1981 type BB is a unique model with a half fairing, similar to the CB900F and a single seat. Comstar wheels, front 19 inch, rear 18 inch.

1982 type BC has plain red and white/blue colour scheme, yellow wing in the logo on the tank and red swingarm. Exhaust is matt black, boomerang wheels, both 18 inch.

1983 type BD has metallic red and white/blue colour scheme, silver logo and a silver square swingarm. Exhaust is black chrome, boomerang wheels as per 1982.

Let's put a hold on the usual machine-head road-test copy for a minute. Motorcycles are obviously much more than machines; they're emotional events. Their engineered aspects are compelling, but they are, at the heart, of the heart.

Motorcyclists may rationalize their tastes in machines in cold-hearted, metallurgical terms, but it's a less than self-aware rider who thinks he buys a motorcycle just because of its quarter-mile times or its cornering clearance or the visual quality of its engine castings.

The Honda CB1100R is one of the select few no-compromise, high-speed motorcycles—machines that express, in visceral as well as functional terms, that their riders are humans of unusual two-wheeled discrimination. Of the roadrace-orient-ed specials in its class the Suzuki Katana, the Eddie Lawson Replica KZ1000R, and the one-liter Bimotas—only the Italian kit.

bikes approach the level of visual flash and exclusivity embodied by the Honda. There are about a thousand CB1100Rs assembled each year for export to Europe, Australia, and South Africa, and getting one, even if you have $9000 to $10,000 burning a hole in your pocket, is a game of musical dealers. If you find the bike, and a dealer who wants to part with it, you have bought yourself the fastest production-line street bike in the world.

| . |

The CB1100R is perfectly suited to the specific kind of motorcycle touring practiced mainly in Europe. Most long-distance riding in the States involves Gold Wings, Harleys, stretched gross-vehicle-weight ratings, and hours of straight-line droning, but on the Continent it's a completely different story. On many routes between major cities there simply are no freeways. The fastest route is often a winding, swooping, roadracer's delight. With speed limits either nonexistent or widely disregarded, much of Europe is a fast street-rider's Nirvana. In west-central Germany it's a popular weekend pastime to make the run out to the Nur-burgring with your girl on the back of your BMW or your Guzzi or your Ducati, the two of you dressed in immaculate racer-replica leathers. For 10 deutsche marks (about five dollars) you can take a lap on the 14-mile course and grind off as much metal from the underside of your bike as you dare; your own tendency for self-preservation is all that holds you back.

Europe is crazy about endurance racing over 150,000 souls make the trek to the 24-hour Bol d'Or every year because their own riding is not so far from endurance racing. Honda has used the European endurance-racing circuit as a proving ground for some of its most popular designs; the engines found in the CB750, CB900, and the CB1100R are directly descended from the power plant used in Honda's RCB racers.

Europeans are much more style-conscious than Americans, and the swoopy FWS-inspired bodywork of the R suits European sensibilities just fine, thank you. If the machine didn't have "Honda" plastered all over it, one would be tempted to imagine it came from some tiny craftsman's shop outside of Turin.

For all its visual impact, the R is surprisingly conventional under its carbon-fiber and Plexiglas skin. The frame is very close to the item used on the garden-variety CB750F, right down to the steering-head angle and wheelbase. Unlike the U.S. 900F, the R's engine is rigidly mounted in the frame; this allows the engine assembly to act as a structural member for added rigidity, at the expense of some extra vibration transfer to the rider. The swingarm appears to be the same unit used on the U.S. 900F, which is by no means an indictment; the stock piece is known as one of the stiffest arms on a production bike.

The frame has one major difference from the familiar CB750F item: the removable frame tube under the right side of the engine has been welded firmly in place on the 1100R, just as it is on the Honda factory Superbikes. This makes engine removal a much more time-consuming proposition, but the gains in chassis rigidity make it worthwhile.

The front fork assemblies are very close to the ones offered on the CX500 Turbo, right down to the TRAC anti-dive unit on each leg, and the front fender is a Turbo part as well. The fork tubes are 39mm in diameter, the same as on the U.S. 900F. The narrow clip-on bars of the CB1100R make it difficult to detect any flex in the front-end assembly; in all our back-road charging the front felt as rigid as a solid block of steel.

The front brake calipers are the same design as used on the Turbo, but the discs are the very slick, internally vented, cast stainless-steel-type used on the CBX. The rear brake is the same as that used on the U.S. 900F, with a twin-piston caliper and a thinner solid disc.

Wheels are of the same gold-anodized aluminum ComStar design as those used on the Turbo, but are different sizes; the rear rim is a very wide 3.00-18, and the front is an equally raceable 2.50-18. Honda recommends only two specific tire choices for the high-speed CB1100R; the bike we tested wore special A48 (front) and M48 (rear) Michelins designed exclusively for the CB1100. There are A48s and M48s available that are not suitable for the big Honda; the specially constructed versions look identical to the standard models except for a special identification mark on the side-wall.

The '81 CB1100R used rear shock absorbers very similar to those offered on our 900F, but the considerably revised '82 comes with all-new shocks apparently exclusively built for the 1100. They're unlike anything we've seen on more familiar Hondas and are independently adjustable for both rebound and compression damping. A knob atop the upper-mounted reservoir provides four stages of rebound damping, and another knob on the bottom of the shock dials in one of three stages of compression damping. It would be possible to adjust the rebound damping while riding if it weren't for the bodywork that shrouds the top of the shock; as it is, adjustment is a reach-in-and-under proposition.

The basics of the power plant are very much the same as the CB750 and CB900. The displacement increase over the 900F is accomplished with a larger bore. The R gets an actual displacement of 1062cc from its 70mm bore and 69mm stroke; the 900F is an actual 901.7cc, with a 64.2mm bore and the same stroke.

Honda went to the trouble of casting new cylinder assemblies for the 1100; 900Fs have air passages between the numbers one and two and the numbers three and four cylinders, but the 1100 is one solid chunk. The 70mm pistons are forged, "semi-forged" to use Honda's terminology, and the wrist pins are 17mm in diameter, 2mm larger than the 900F's. The valve train, valve sizes, and combustion chamber design are the same on the 1100, with the exception of the cam timing. The 1100 cam is a mildly hot-rodded configuration which opens both the intake and exhaust valves about 10 degrees of rotation sooner and closes them 10 degrees later, with an attendant increase in lift.

The U.S.-version 900F has a mild 8.8:1 compression ratio, which allows it to run on anything more volatile than peanut oil. The 1100R is intended for countries that still have real gasoline available; its compression has been bumped up to 10.0:1. The owner of the bike we tested preferred to run 120-oc-tane aviation gas in his pride and joy, but we did manage to run one tankful of 92-octane leaded premium through without any sign of detonation.

The carburetors of the 1100 look very much like the Keihin CV units that come on the 900F, but they're actually one millimeter larger inside than the 900F's 32mm mixers.

The extra power provided by the displacement increase and the wilder cam timing necessitated a few other changes. The link-plate primary chain is wider, the bearing inserts are harder (for longer life under racing conditions), and while the clutch plates are stock 900F, the springs are stiffer.

The stock Honda transistorized battery ignition has been known to be less than adequate when the revs start climbing toward five figures, and the 1100 uses a modified version of the same basic system, housed under a formfitting, gold-painted cover. The alternator cover has been pre-beveled for your cornering convenience.

Transmission ratios are the same as those on the 900, but the final reduction ratio is taller; at redline in fifth a 900 should go 140 mph; the 1100R is geared for an eye-opening 155.

Looks are a very big part of the CB1100R mystique, and the combination of the 'exotic composite full fairing, the Formula One-style single seat, the hunched-over riding position, and the wild paint treatment stopped bystanders in their tracks wherever we rode the beast. The '81 R used the same upper fairing you could order for your U.S. 900F, but the '82 edition uses a new two-piece fairing, reportedly laid up using some of the hideously expensive carbon-fiber cloth used on Honda's F-1 bike body parts. The cost, as they say, is passed on to the consumer: the price we were quoted to replace the fairing was a princely 2000 clams. The bottom section of the fairing comes off in a matter of seconds for easy access to the engine; taking off the top half is a bit more complicated, but it's still only a 15-minute proposition.

The seat and tail section are also new this year. They're a very clever combination of a solo seat with a backrest and a coventional dual seat; a twist of a few Dzus fasteners allows the tailpiece to be lifted off the bike, exposing the rear half of the red saddle.

If you should be fortunate enough to make a friend while out on a solo ride, however, it's anybody's guess what you're supposed to do with the removed tail section. To avoid having to UPS part of your motorcycle home from a ride, it's suggested you leave the tailpiece behind any time you're feeling lucky.

The racer-replica seat is thin and hard, but the hunched-forward, clip-on-dictated riding position and the rearset pegs allow much of the rider's body weight to be earned by his legs over bumpy sections of road. The beautiful 6.9-gallon aluminum fuel tank stays out of the way of the rider's knees; our longer-legged testers only wished they could say the same about the rear edges of the lower fairing section. Under hard braking and in certain hanging-off maneuvers, it was entirely possible to run out of knee room.

The aluminum clip-ons are higher and wider than the units used on the Suzuki Katana and are mounted above the triple clamps on the protruding ends of the fork tubes. They can be adjusted by swiveling them around on the tubes, and by loosening one bolt on each side, a certain amount of droop adjustment is also possible. However, the clearance limits of the fairing dictate the range of adjustment.

The seating position is surprisingly comfortable for a race-bred machine; Honda's ergonomicists apparently spent quite a bit of time juggling the seat, footpeg, and handlebar positions to make sure no one part of the rider's anatomy was called on to do more than its load-carrying share.

The controls and instruments are standard European Honda pieces; an electronic tach replaces the mechanical unit found on our 900F, and the speedometer, of course, reads out all the way past 150 mph.

Our usual road-testing sequence lasts quite a few days, with each staffer getting a chance to form a relationship with the machine in question. The R wasn't just another in a manufacturer's fleet of test bikes, though; it had a real, live, flesh-and-blood owner, and he was with us every step of the way, concern (or was it terror?) written all over his face.

The R is surprisingly docile and manageable in slow city traffic. The low seat height makes it easy to relax at stoplights, as you drink in the admiring glances of mere pedestrians. With no EPA smog rules to mess up the carbure-tion, the 150-mph Honda is, if anything, more driveable than most American-spec Japanese street bikes; the characteristic off-idle lean surge we've all learned to accept on other bikes just isn't there. The engine gives no sign of its capacity for heavy horsepower production within the city limits. It's smooth, torquey, and relatively quiet, even with the single-wall exhaust header pipes.

With the same steering-head angle and wheelbase as the 900F, we expected light steering and rock-solid stability when we got the R out on the open roads. The stability is there, but the steering is surprisingly slow; the leverage lost with the narrow clip-ons makes it change direction very deliberately.

Riding the 1100R quickly took some getting used to. More than any other sporting street bike in recent memory, the R wants to stand up, and hard, if the rider trails the front brake into corners. This is a function of the very wide tires' offset contact patches; braking weight transfer wants to act through the center of the tire. When the bike is leaned over, the distance between the contact patch and the center of the tire creates quite a substantial lever arm, which tries to pull the bike upright. On other street bikes with wide tires, the front suspension is set up soft enough to make the stand-up tendency less abrupt, but with the 1100R's taut suspension the effect is quite pronounced. We soon learned to keep our fingers off the lever any time we wanted to flick the big Honda into a corner quickly.

The special Michelins offer impressive grip, but their transition from straight up-and-down to their cornering contact patches feels a little less than confidence-inspiring. They like to be going straight or cornering hard. It's almost as if the tires were impatient with anything short of full racetrack speeds.

The machine's cornering clearance is seemingly unlimited. After you've leaned the bike over about five degrees farther than you think is prudent, you start begging to feel something, anything, touch down, just to give you some indication that there's still a road down there somewhere. We still had a little unused cornering tread on the edges of the Michelins at the end of our testing, so it's quite possible that a CB1100R owner with more brio than brains will manage to touch the peg feelers down before he runs out of tire. However, with the owner of our very expensive R standing watchfully by during photo sessions, we were not about to press the issue.

In high-speed corners, just as advertised, the CB shows what it was built to do. Its narrow bars, huge tires, and relatively slow steering geometry make it feel very stable and confidence-inspiring in triple-digit cornering. The suspension rates, both front and rear, feel a bit stiff in slower going on bumpy canyon roads, but when the speeds come up, everything works together like the Lakers on a May night. On trailing throttle, the CB showed a tendency to fall into the slower corners a bit, but at higher speeds the chassis stayed delightfully neutral all the way through the longer sweepers.

The ventilated front brakes worked as well as any street-oriented brakes have a right to. The brakes could probably be made to fade with hard use on the right racecourse, but we never even came close. The CB1100R carries its weight much lower than the CX500TC does, making the anti-dive apparatus built into the fork sliders less necessary than it is on the Turbo. We settled on the number two (of four) anti-dive setting for most of our fast canyon work.

We had a Suzuki GS1100E along on each of our testing sessions with the CB1100R, and we couldn't resist the temptation to see how the big Honda would fare against the king of U.S.-legal street-bike acceleration. With riders of roughly equal weight aboard, the two bikes were very closely matched; the Suzuki was notably faster in the lower half of its rev band, but the two bikes ran dead even with both engines in the fat parts of their powerbands.

Our dragstrip testing confirmed the results of our seat-of-the-leathers testing. On a day much too hot for any record-setting times, the CB1100R posted the fastest ET of any 1100cc 1982 street bike we've tested: a run of 11.41 seconds at 118.73 mph. On a cool day, with a tailwind and with aptly named PeeWee Gleason on board, we've run an '81 GS1100 as fast as 11.001 seconds at 121.45, with a Kawasaki GPz1100 right behind with a 11.017-second run at 122.1. The CB1100R was only halfway through fourth gear at the end of the quarter-mile, so with slightly shorter gearing the CB would be hard to bet against on any given day at the strip.

In fifth-gear roll-ons the CB was considerably slower than both the GS1100 and the GPz1100, which was no surprise; the Honda makes its power a little higher in the rev band, and it is, after all, geared for an extra 15 mph of top speed.

We tried to get the CB to its top speed, or close to it, by taking a running start at the starting line at Orange County Raceway and holding the butterflies open for a full half-mile run. The highest indicated top speed we got was 141 mph, with a

MOTORCYCLIST OCTOBER 1982

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |