|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

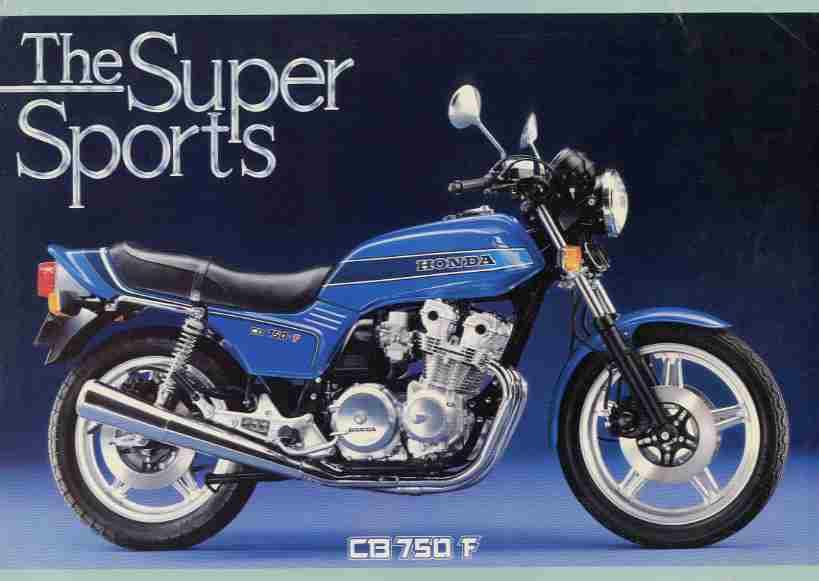

Honda CB 750F-Z Bol d'Or |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Honda CB 750F-Z Bol d'Or |

|

Year |

1979 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, transverse four cylinder, DOHC, 4 valve per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

748 cc / 45.6 cub in |

|

Bore x Stroke |

62 x 62 mm |

|

Compression Ratio |

Air cooled |

|

Cooling System |

9.0:1 |

|

Induction |

4x 32mm Keihin carburetors |

|

Ignition |

CDI |

|

Starting |

Electric |

|

Max Power |

57 kW / 77 hp @ 9000 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

77,4 Nm / 57.0 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

|

Final Drive |

Chain |

|

Front Suspension |

Adjustable telehydraulic fork |

|

Rear Suspension |

Swinging arm fork with adjustable shocks absorbers |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 276mm discs |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 297mm disc |

|

Front Tyre |

3.50 H19 |

|

Rear Tyre |

4.50 H17 |

|

Trail |

115 mm / 4.5 in |

|

Wheelbase |

1520 mm / 59.8 in |

|

Seat Height |

790 mm / 31.1 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

140 mm / 5.5 in |

|

Dry Weight |

230 kg / 507 lbs |

|

Wet Weight |

251 kg / 553.3 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

20 Litres / 5.2 US gal |

| Standing ¼ Mile | 12.4 sec / 172 km/h |

| Top Speed | 198.3 km/h / 123.2 mph |

| Road Test | Cycle |

| . |

Road Test MOTORCYCLIST 1979

Ever since the Japanese motorcycle firms rose from their 50 and 90cc machines to build genuine motorcycles, it has been axiomatic that Oriental street bikes, despite whatever other pinnacles they reached, always lagged behind the Europeans in that one virtue most important to purists: Handling. Their handling habits ranged from downright horrifying on a few models to the more common characteristic, a slight vagueness in steering accompanied by not enough ground clearance. "Too much power," proclaimed some observers. "Bamboo frames," said others. "Too many cylinders and too much weight," added other voices. "The basic problem," many agreed, "is that the Japanese company executives and engineers don't ride motorcycles. They have no passion for them so they don't understand how they're supposed to handle. And they don't care. They'll GS750, and especially their GS1000, destroyed the Japanese-bikes-don't-handle maxim forever and they did it with four cylinders, a truckload of power and a weight that solidly crested the quarter-ton mark. Purists could suddenly enjoy Ducati-like cornering prowess with typical Japanese power, comfort, price and dealer support. The cynics had to find something else to gripe about.

As if to prove the GS1000 was no fluke, in 1979 Honda launched their new DOHC CB750F, which if anything handled better than the big Suzuki. Unfortunately, the Honda's handling began to erode as miles were rolled up on the machine. By the time we'd put 2000 miles on our '79 test bike, we noted a slight loosening of the swingarm pivot and a substantial drop in rear suspension performance. The bike still handled quite well, but we were disappointed by such signs of corner-cutting in a manever build a really good handling motorcycle because they just don't need to."

That

sort of thinking about motorcycles from Japan began to look a little tarnished

when Honda's 400 and 550 fours arrived. Then Suzuki's chine which was otherwise

so spectacular. Those drawbacks didn't seem to matter much though: Honda had

sold out of CB750Fs by July.

That

sort of thinking about motorcycles from Japan began to look a little tarnished

when Honda's 400 and 550 fours arrived. Then Suzuki's chine which was otherwise

so spectacular. Those drawbacks didn't seem to matter much though: Honda had

sold out of CB750Fs by July.

Because the 1979s were all gone, the 1980 CB750F was introduced early, and we are delighted to see that Honda has made improvements in both areas where the 1979 model came up short. By providing needle bearings at the swingarm pivot, Honda has virtually eliminated any wear and subsequent swingarm looseness. Even more impressive are the new Fully Adjustable FVQ shocks which feature separate adjustments for compression and rebound damping in addition to the usual choice of five spring preload settings. Changes in other areas further improve handling. The frame has added gusseting in the swingarm area and a larger swingarm pivot bolt (increased in diameter from 14 to 16mm) adds brawn. The fork tubes' offset in the triple clamps is now increased a shade to reduce front wheel trail by 5mm to make it 110mm.

The most interesting of these changes is the new Fully Adjustable FVQ (Full Variable Quality) shocks which are the most adjustable shocks ever offered on a street bike. An adjuster wheel at the top of each shock allows the rider to pick one of three settings for rebound damping. The adjusting wheel is operated by the same spanner used to adjust spring preload. At the bottom of each shock, a small lever nestled in the mounting clevis may be flicked to either of two settings to vary compression damping. During serious pitch-it-off-into-corners riding sessions we usually used the middle rebound setting, the stiffer compression adjustment and the spring preload set on the second or third step up. For the best ride in terms of comfort, backing all the adjustments down to their softest settings seemed to be the ticket.

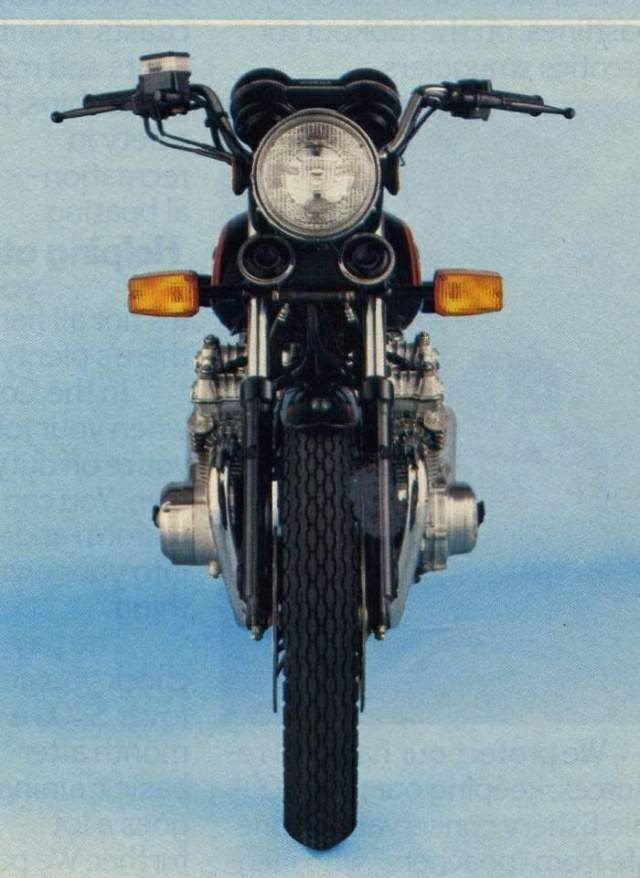

When this 1980 model was introduced, we wondered aloud why Honda didn't opt to include air forks. After riding it, we admit that we didn't really miss them. Front-end dive wasn't a problem and overall handling was universally rated as good as or better than anything ever offered for street use. No matter if the corners are bumpy or smooth, fast or slow, the F can rush through them with no trace of wiggle or wallow, and only an occasional scrape of the pegs on the pavement. The bike is as precise and steady as a brain surgeon's scalpel and changing lines in mid-corner is easy.

We had an opportunity to ride the 1979 and 1980 models side by side and noticed that the new bike was a little steadier than last year's which was quite steady to begin with. Bumps seemed softer and smaller on the '80 model too. No one commented on any change in steering feel with the slight change in front wheel trail, but steering was inordinately accurate. The new CB750F's handling is a special treat for the expert street rider, and a novice may find he has abilities he never knew he possessed. Anyone who still believes that Japanese bikes or four-cylinder machines can't handle is in for a tremendous surprise.

Our 1980 F had racked up over 1800 miles by the time we returned it and there was no sign of the shocks fading away or any looseness in the chassis. The CB750 was as tight and wiggle-free as when we got it.

Another common problem on last year's Hondas was an annoying brake surge which developed after the brakes had been used hard a few times. Honda says this was caused by a quality-control problem which has been corrected through a different brake disc surfacing process. Our test machine's brakes didn't surge and performed excellently. A novice may be overwhelmed by the F's powerful triple discs, but the expert will appreciate the bike's strong, predictable, fade-free stopping.

The DOHC four-valve-per-cylinder engine returns with no significant changes. The four 30mm constant-velocity carbs provide typically abrupt response when the throttle is first opened and we noted a slight surging when the air was cold and dense. This engine surging is not uncommon in new models because of their government-mandated fuel mixtures. Aside from these minor criticisms and complaints about lash in the lower gears, we were very pleased with the F's power delivery. It has enough low and mid-range power to pull away from traffic quickly without a downshift. However to take advantage of all its enormous power, the rider must spin the motor right up to the 9500-rpm redline. Power is definitely concentrated in the upper half of the powerband.

When we tested the 1979 model seven months ago, we noted quite a bit of chain noise. Honda responded to this complaint by fitting a smaller chain with bigger sprockets. The 630 chain (%-inch pitch) was replaced by an O-ring type No. 530 chain (%-inch pitch). Noise was the primary reason for this change and chain noise has been substantially reduced, although not eliminated. The 1979 CB750F which won this year's 24 Hours of Nelson Ledges did so with the stock 630 D.I.D. chain which was 2000 miles old at the start of the race and went the distance without any external lubrication and only one adjustment. We wonder if the 530 is as durable. Since the 530 has relatively larger sprockets (18 and 46 teeth for a ratio of 2.56:1) than the 630 did (15 and 38 teeth for a ratio of 2.53:1) it doesn't have to turn as tightly and therefore may prove as tough as the larger chain. The bigger sprockets certainly make it quieter and the tiny change in gearing isn't noticeable when you ride the old and new models together. Since it's lighter, the 530 chain theoretically saps less power (which is why drag racers usually replace 630 chain with 530).

The chain and gearing switch is the only drivetrain change, so performance is about the same as the '79. The bike still turns a lot of rpm (about 4600) at 60 mph in fifth and it still rips off lightning-quick quarter-miles (12.46 seconds at 106.9 mph as compared to 12.33 seconds at 108.8 mph for the '79 model). The 1980 bike averaged 37.8 mpg.

One problem we had on this bike that didn't occur on last year's machine was a slight shifting malady. This bike frequently missed upshifts from first to second gear. Sometimes it took two shifting movements before it would upshift.

Sporting bikes are often about as plush as a sawhorse, but the 1980 750F is fairly comfortable. The ride has been improved a hair and the overall comfort is quite acceptable for two- or three-hour trips. All-day drones on the Interstate may prompt disparaging remarks about the saddle, but neither it nor the bike were built to specialize in open-road touring. Passengers quickly complained about a hard seat, awkWard footpeg placement and a mild vibration in the rear pegs.

The "reverse" black ComStar wheels have apparently proven more popular than Honda's original configuration, so that's what carries the 1980 F. The wheels are all aluminum alloy and mount Dunlop tires, which are tubeless for extra blow-out protection and weight reduction. The bike's paint schemes are essentially the same as last year with either black or silver as the basic colors and new striping colors. The turn signals are now black.

A depressing change is the 85-mph speedo, something we'll be seeing a lot of in 1980 thanks to some government bureaucracy's notion of safety.

We were very impressed with the 1979 CB750F, but we're dazzled by the 1980 version which has no nagging little flaws left in its make-up. We're even more impressed because the price has gone up just $53—less than what you'd pay for a good pair of shocks. Although touring riders may shy away from the Super Sport, it's an exciting choice for sporting riders who have the competence, inclination and experience to use and appreciate its power and handling.

One of our staffers rates the new F as "the best street bike there is," and the rest of us rate it as tied with or second to the Suzuki GS1000. The Suzuki is a little more versatile because of its extra torque and comfort. However, it's also more expensive. There's one more thing you should know: Honda is expected to have a 1000cc version of the F out this spring. We can hardly wait. M

Source MOTORCYCLIST 1979.

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |