|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

Honda VF 750F Interceptor V45 |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Honda VF 750F Interceptor V45 |

|

Year |

1984 |

|

Engine |

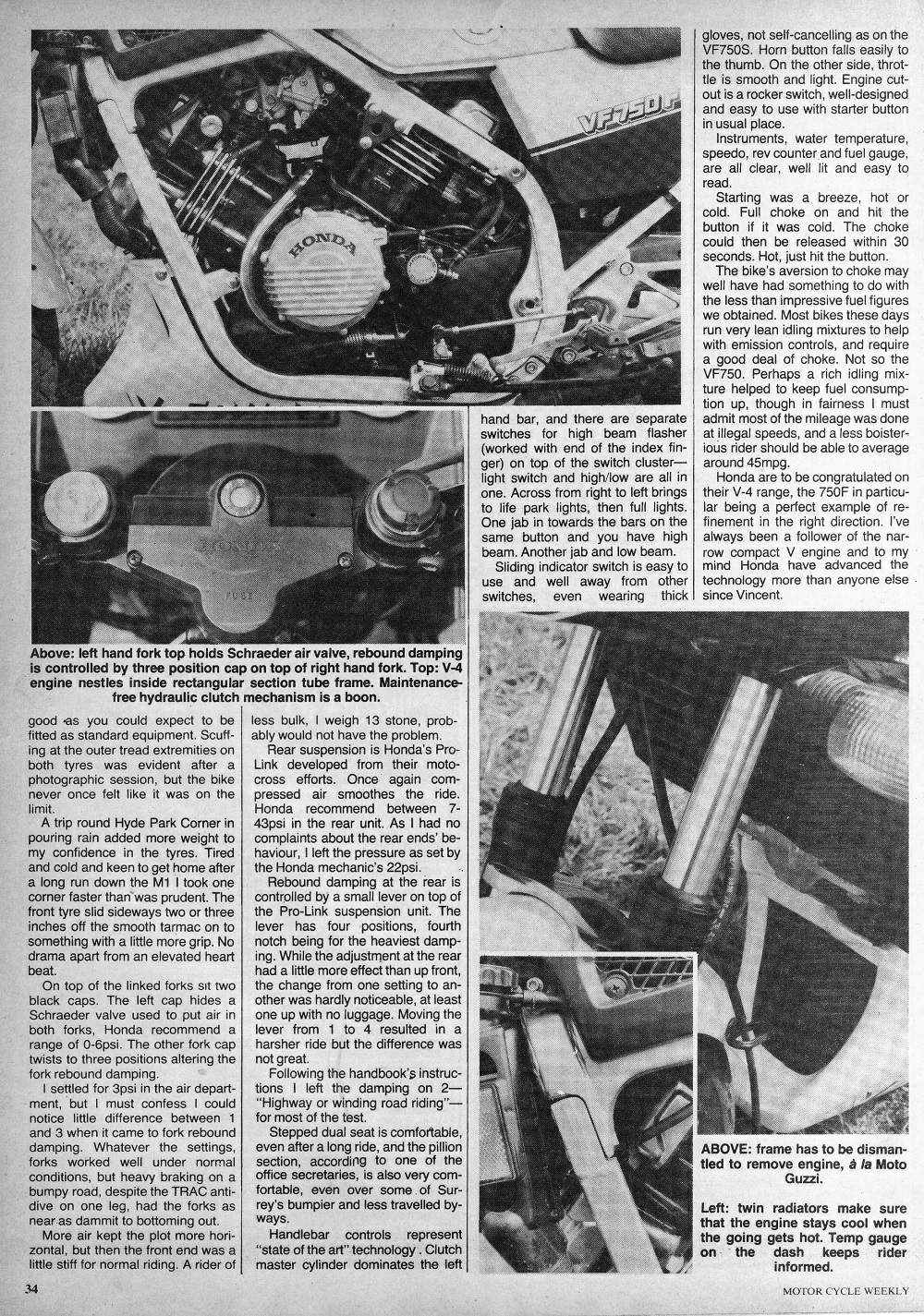

Four stroke, 90° V-four cylinder, DOHC, 4 valve per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

748 cc / 45.8 cub in |

|

Bore x Stroke |

70 х 48.6 mm |

|

Compression Ratio |

10.5:1 |

|

Cooling System |

Liquid cooled |

|

Lubrication |

Wet sump |

|

Induction |

4 x 30mm Keihin carburetors |

|

Ignition |

Transistorized |

| Charging System | 12-Volt 300 watt alternator, voltage regulator / rectifier, 14 ampere-hour battery |

|

Starting |

Electric |

|

Max Power |

64.1 kW / 86 hp @ 10000 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

62.7 Nm / 6.4 kgf-m / 46.3 lb-ft @ 7500 rpm |

|

Clutch |

Wet, multiplate, with one-way overrun clutch |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Primary Drive | Straight-cut gears; 2.588:1 ratio |

|

Final Drive |

#530 O-ring chain (5/8-inch. Pitch, 3/8-inch width); 2.588:1 (44/17) ratio |

|

Gear Ratios |

1st 2.733 15.222 5.02 2nd 1.895 10.555 7.24 3rd 1.500 8.355 9.15 4th 1.240 6.907 11.07 5th 1.074 5.982 12.78 |

|

Frame |

Box section and round mild steel tubing, double front downtubes |

|

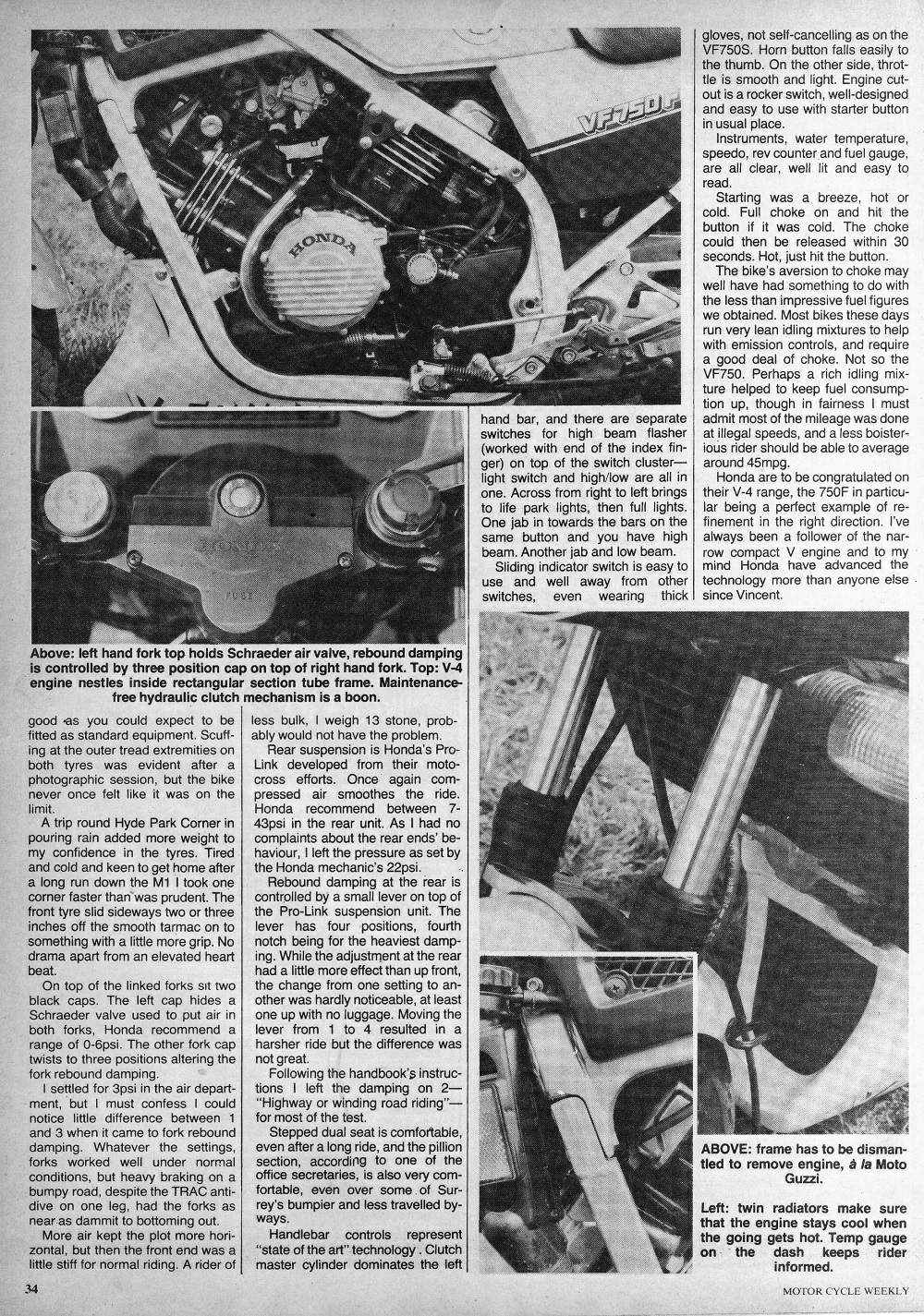

Front Suspension |

Showa air spring, 39mm stanchion tube diameter, 3 position adjustable rebound damping, brake-actuated hydraulic anti-dive |

|

Front Wheel Travel |

154 mm / 6.1 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Single Showa air-spring shock, 4-way adjustable rebound damping |

|

Rear Wheel Travel |

112 mm / 5.1 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 270mm discs |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 288mm disc |

|

Front Tyre |

120/80-16 |

|

Rear Tyre |

130/80-18 |

|

Wheelbase |

1514 mm to 1544 mm / 59.6 in to 61.3 in |

|

Seat Height |

820 mm / 32.3 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

155 mm / 6.1 in |

|

Dry Weight |

221 kg / 487 lbs |

|

Wet Weight |

248 kg / 547 lbs |

| Fuel Capacity | 19 Liters / 5.0 US gal |

| Standing ¼ Mile | 11.9 sec / 180 km/h / 112 mph |

|

Top Speed |

216 km/h / 134 mph |

|

Road Test |

Cycle Magazine 1983 |

| . |

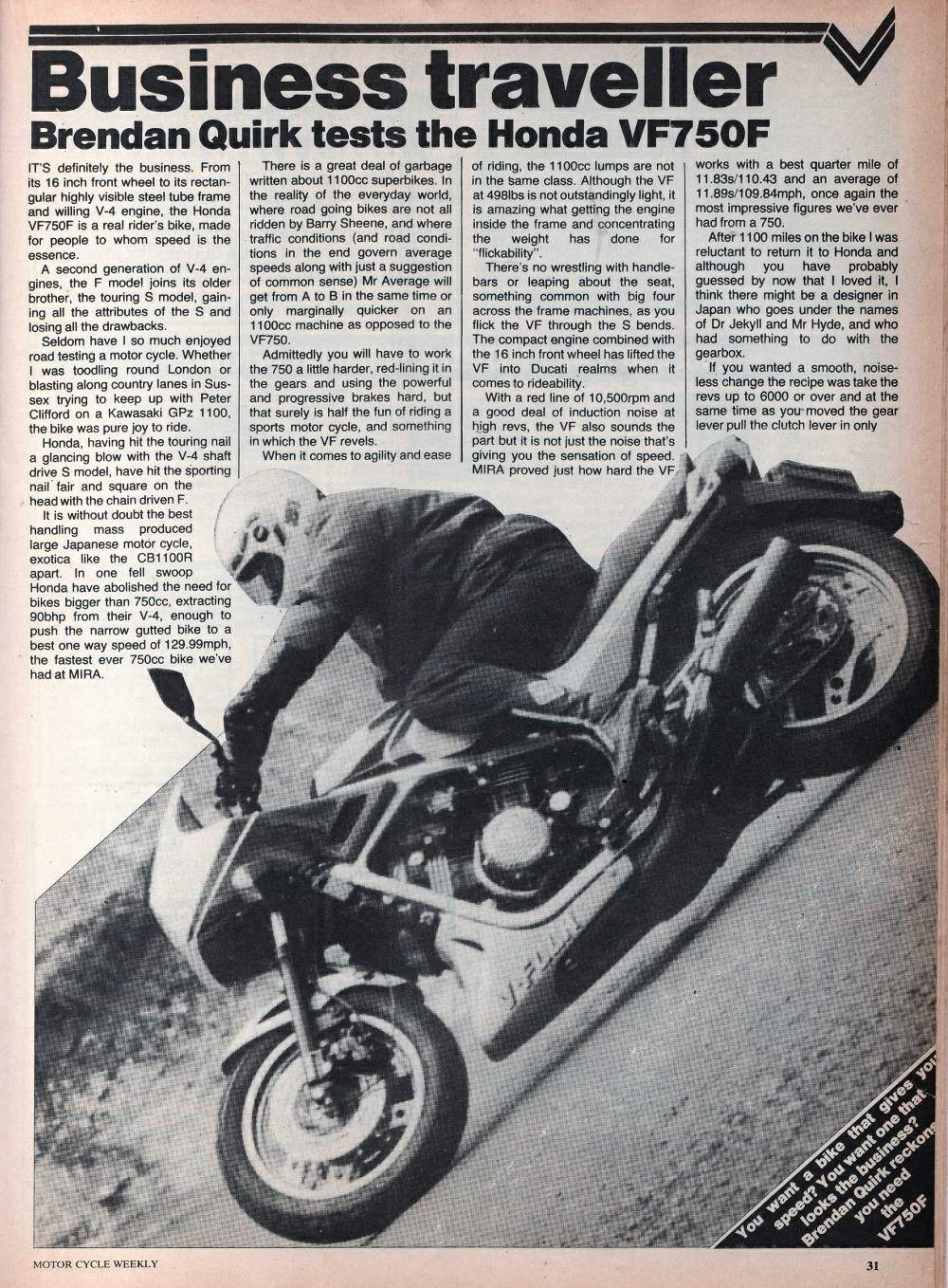

An Interceptor is a fighter aircraft specifically designed to repel enemy missions. Relying on high speed and powerful armament, they were once seen as the first line of air defense. So did Honda’s first Interceptor, the 1983 VF750F, have the fleetness and firepower necessary to beat the competition?

It’s been said that Honda rushed its V4s to market after the launch of the Suzuki Katana, and in anticipation of a new world-beater from Yamaha that became the FJ1100. As the Eighties dawned, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha seemed bent on deposing Big Red as the default Japanese brand. Honda appeared to have taken its eye off the ball, perhaps because of its new range of four-wheelers. Its mainstream bikes were seen as sturdy and reliable, but stodgy and dated. While Honda relied too long on its single overhead cam design from 1969, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki, formerly 2-stroke dependent, had all developed dual overhead cam inline 4-stroke fours. Though technological tours de force, neither the Honda Gold Wing, nor the CBX — not to mention the CX twin — were considered mainstream: Honda’s volume marketplace lead was slipping.

Then the V4s arrived, like a squadron of F-22s to intercept and scatter the intruders, creating a sensation along the way. In 1982, Honda introduced the V45 Sabre and Magna for the U.S. market, and the VF750S for Europe. All had liquid-cooled, hugely over-square 70mm x 43mm bore and stroke engines, 6-speed transmissions and shaft drive. The short stroke, 4-valve V4 was state of the art, and buyers anticipated high-revving, high-power performance.

The VF750F joined the U.S. range a year later, in 1983. Aping Suzuki’s 1981 Katana, the VF sported a frame-mounted headlight fairing. But while the Katana was in many ways a dressed-up late-Seventies GS1100, the Honda was just about all new. Though based on the V45 Sabre, the VF featured an all-new GP-derived frame, a revamped power train and several other race bike goodies.

The Honda VF750F Interceptor was the offspring of a metaphorical marriage between the revolutionary 996cc V4 FWS1000 U.S. Formula 1 Championship Superbike racer Honda introduced in 1982 and a change in AMA Superbike rules. For the 1983 season, 4-cylinder bikes were limited to 750cc and were required to be production based. Honda management decided to build a new street bike around the Sabre engine, but with the right stuff to form the basis of a Superbike contender. The 1983 Honda VF750F Interceptor was the result.

The innovations were immediately apparent. An all-new perimeter frame made from square-section steel tubes enveloped a strengthened version of the 750cc V4, which was tilted back to allow for a shorter wheelbase and better weight distribution. The VF750F engine shared most components with the Sabre, though detail changes to cam timing and combustion chambers resulted in extra horsepower. A more race-suitable chain final drive replaced the Sabre’s shaft, while the number of cogs in the transmission went, curiously, from six to five. Apparently, reconfiguring the tranny for chain drive meant less room for gears, and rather than make the gears narrower, which would increase their loading to an unacceptable level, Honda chose to drop one.

The transmission also included a new slipper clutch, with half of the clutch plates driving the clutch hub through sprags, so the clutch was only 50 percent effective on the overrun. This provided for some slippage if rear wheel traction was compromised under heavy braking. And here you thought slipper clutches were something new.

Using similar engine internals to the Sabre meant the Interceptor retained the Sabre’s chain drive to the four overhead cams, carrying forward tensioner and cam wear problems that were just showing up on the 1982 bikes. Though Honda had developed a multi-gear camshaft drive for their V4s, it was reserved at that time for the European-market VF1000R. But in 1983, the issue of cam wear had yet to make the front page.

Completing the racer-on-the-road formula was a 16-inch front wheel attached to fully adjustable, air-assist Showa forks fitted with Honda’s TRAC anti-dive system. Sixteen-inchers were all the rage on the track, though whether the faster-turning characteristics were a result of reduced rolling mass and radius or a shorter steering angle was open to argument. Rear suspension was Honda’s own Pro-Link system with a fully adjustable air-assist Showa shock. Comcast alloy wheels (the demise of the sketchy composite Comstar wheels from the CBX era disappointed no one) carried floating discs, two at the front and one at the rear, each gripped by twin-pot calipers.

As well as the prodigious thrust provided by 77 rear-wheel horsepower (Honda claimed 86 at the crank), testers noted that the Honda VF750F Interceptor was a Japanese Superbike with a chassis that really and truly handled. Unlike the rubber-mounted Sabre engine, the Honda Interceptor engine bolted directly to the wide perimeter frame, providing very effective cross-bracing. The well-triangulated steering head, rigid cast alloy swingarm and cross-braced front fork also helped resist twisting loads. The inclusion of 4-stop, adjustable preload for the rear suspension and adjustable air assist at both ends provided dial-in settings to optimize springing and damping for the weight of the rider and for the type of surface — including the racetrack.

So was the VF750F just a repli-racer on the street like today’s screaming 600s — peaky power, nervous steering and a 20-minute riding position? Not according to period reports: An “incredibly docile powerplant” combined with “a fine balance in the location of seat, bars and pegs” to produce “a supremely versatile motorcycle, one that’s neither a posturing dandy with delusions of trackside grandeur nor a surly, petulant racer-cum-roadster,” said Cycle Guide of May 1983. “Steering response is textbook neutral,” it went on, making the Honda VF750F Interceptor “as useful to the Monday-through-Friday commuter as it is to the Sunday morning racer."

But there was trouble in paradise. Issues with rapid camshaft wear and disintegrating cam chain tensioners started surfacing regularly, and Honda’s belated response was a series of service advisories that attempted band-aid solutions under warranty rather than a full recall. Unfortunately, the damage to the VF’s image was done, and within two years the VF750F was replaced by the VFR750 with gear-driven cams and a twin-spar alloy frame.

The original Honda Interceptor had itself been intercepted.

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |