|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

Ducati 750 Paso

|

| . |

|

Make Model |

Ducati 750 Paso |

|

Year |

1986 - 87 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, 90°“L” twin cylinder, SOHC desmodromic 2 valve per cylinder, belt driven |

|

Capacity |

748 cc / 45.6 cu in |

| Bore x Stroke | 88 x 61.5 mm |

| Compression Ratio | 10:1 |

|

Induction |

Weber 44DCNF 107 carburetor |

|

Spark Plugs |

Champion RA6YC |

|

Ignition |

Kokusan electronic |

|

Battery |

Yuasa 12V 14Ah |

|

Starting |

Electric |

|

Max Power |

53.3 kW / 72.5 hp @ 7900 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

70.4 Nm / 7.2 kgf-m / 52 ft-lb @ 7000 rpm |

|

Clutch |

Dry, multiplate |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Primary Drive Ratio | 1.972:1 (31/71) |

| Gear Ratios | 1st 2.500 / 2nd 1.714 / 3rd 1.333 / 4th 1.074 / 5th 0.966:1 |

|

Final Drive Ratio |

2.533:1 (15/38) |

|

Final Drive |

Chain |

|

Front Suspension |

42 mm Marzocchi M1R fork |

|

Rear Suspension |

Marzocchi super mono rising rate swingarm |

|

Front Brakes |

2 x 280 mm Discs |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 270 mm disc |

|

Front Tyre |

110/90 -18 |

|

Rear Tyre |

140/90 -15 |

|

Dimensions |

Length: 2032 mm / 80.0 in Width: 655 mm / 25.8 in Height: 1150 mm / 42.3 in |

|

Wheelbase |

1450 mm / 57.1 in |

|

Seat Height |

780 mm / 30.7 in |

|

Dry Weight |

195 kg / 430 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

22 L / 5.8 US gal / 4.8 Imp gal |

|

Consumption Average |

5.4 l/100 km / 18.6 km/l / 43.7 US mpg / 52.5 Imp mpg |

|

Top Speed |

210 km/h / 130.5 mph |

|

Colours |

Red, white, blue |

| Road Test | Cycle World |

| . |

Overview

What Was So Special About The Ducati Paso?

Another Massimo Tamburini Ducati that deserves a place in the hall of fame.

When unveiled in 1986, the Ducati Paso 750 represented a high point in

motorcycle design with its sleek, functional, fully enclosed bodywork. There was

nothing quite like it.Bruno dePrato

In the mid-1980s, the Castiglioni brothers, Gianfranco and Claudio, owned the Cagiva Group and had established excellent ties with the leaders of the major Italian political parties. They liberally used their connections to financially strengthen the group after proving rather successful both in the motorcycle market and on racetracks. These same friends granted the Cagiva Group full control of Ducati at no cost. Not a bad gift.

At the time, Ducati was controlled by a government-owned financial group, and the top managers were so inept that heavy financial losses piled up year after year. Giving it to the Cagiva Group at least cut the hemorrhagic flow. Almost in perfect coincidence with the acquisition of Ducati, Claudio had made a generous offer to Massimo Tamburini, rescuing him from the backstabbing that Massimo had received from his former Bimota partner, Giuseppe Morri. Claudio and Massimo teamed up perfectly, and Claudio entrusted Maestro Massimo Tamburini with the design and development of the new Cagiva and Ducati models.

Ducati was limping badly with its line of models, and Claudio first discussed with Massimo the creation of a model that would radically refresh the company’s image—starting with a breathtaking design, the Massimo Tamburini way. It would be called Paso, for the Aermacchi/Harley-Davidson champion Renzo Pasolini, who died in a terrible crash that also killed Jarno Saarinen on the first lap of the 1973 Italian 350 Grand Prix at Monza.

Tamburini’s mission was a big challenge because the new model had to retain the essence of a real Ducati, with levels of dynamic qualities, styling finesse, comfort, and practicality never achieved before at Borgo Panigale. Tamburini wanted the new model fully wrapped in a sleek fairing that should also grant high-speed comfort.

Ducati Paso

Perfectly balanced, the Ducati Paso was a great ride, both on the road and at

the racetrack.Bruno dePrato

The 750cc OHC Pantah V-twin that would power it was a radical evolution over the previous generation of bevel-driven OHC Ducatis. Dr. Fabio Taglioni had replaced the traditional interference-fit built-up crank assembly turning on roller bearings with a much more reliable solid crankshaft with cap-type connecting rods turning on plain bearings. But still he selected a hybrid solution at the main ends, not plain bearings but the same MRC high-performance angular contact ball bearings that I had selected for the glorious 750/900SS in my days working at Ducati with the great Doctor T. That he still selected them for the Pantah engine I took as an appreciation of a job well done back then.

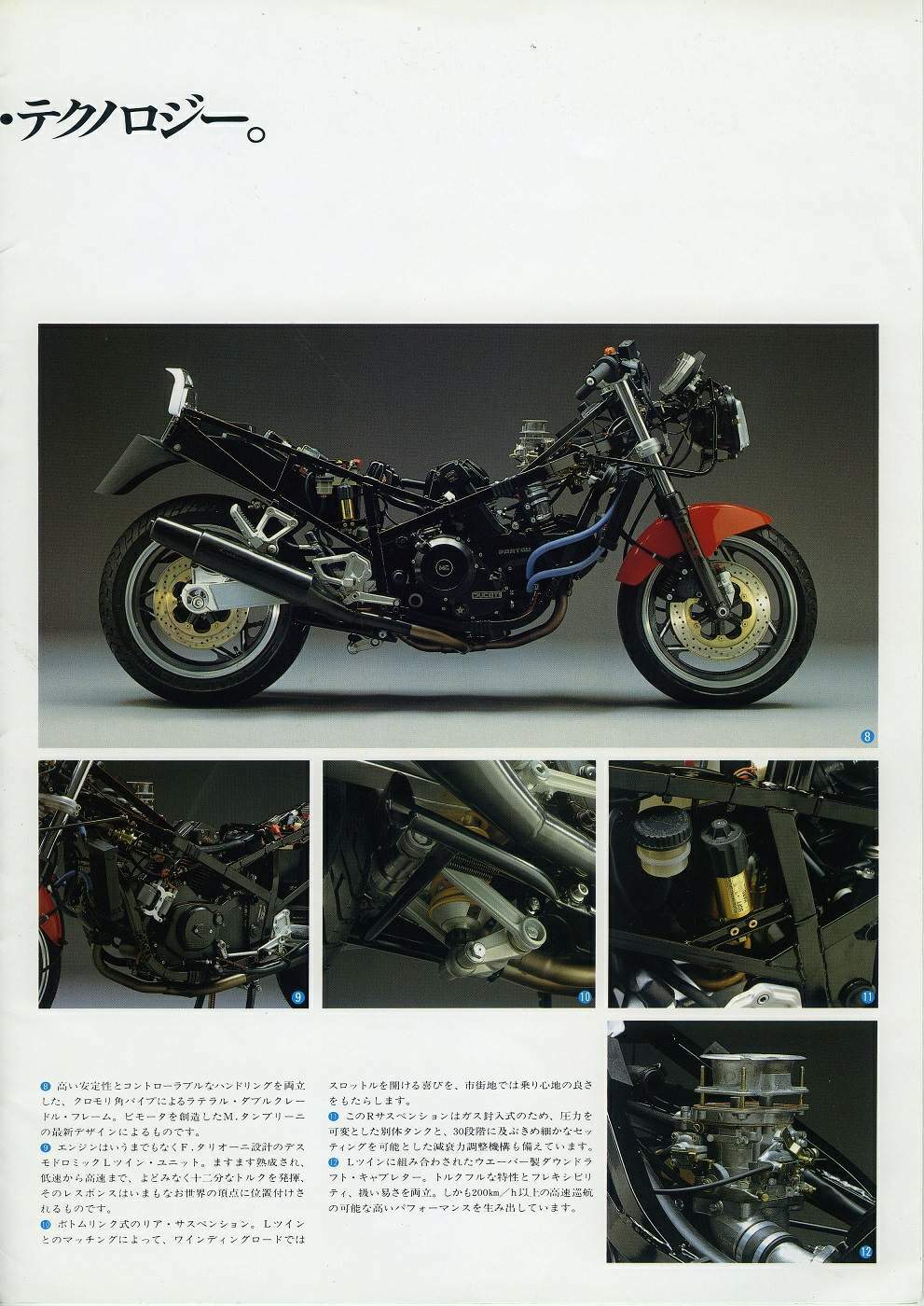

The sleek, fully faired design Tamburini chose gave him a free hand on frame design, allowing him to make it easier to fabricate (its square tubes welded more easily) and faster to build a bike around on the assembly line. A bolt-in lower cradle gave easy access to the engine for servicing, rather than requiring engine removal as did other Ducatis of the day.

The solid and functional frame structure was nothing compared to the radical

revolution Tamburini made in frame geometry. Tamburini never loved any of the

previous Ducati chassis for their rear-biased weight distribution and heavy

steering geometry. He progressively refined every minor geometric factor of his

project to the point that the Paso still is the best-balanced Ducati chassis

ever, even today.

square steel tubing frame

Tamburini conceived a square steel tubing frame structure to simplify the

production process, and accurately calculated steering geometry and

weight-distribution bias.Bruno dePrato

To obtain this precious result, he took advantage of the latest innovations, among them radial tires. Michelin and Pirelli had both developed low-profile 16-inch radials. The 130/60-16 front radial was 22 inches in diameter, a cool 1.58 inches less than today’s standard 120/70-17, and much more compact when compared to the 18-inch tires of the original Pantah.

Keeping the Pantah chassis as a reference, Massimo pulled the steering rake down from 31 to 25 degrees and 95-millimeter trail, but above all, he fully exploited the advantage offered by the much smaller diameter of the new front radial, and retracted the front wheel by more than 2 inches nearer to the center of gravity while adding 2.5 inches to the swingarm, a total geometrical revolution that generated a perfectly balanced chassis spanning a still pleasantly compact 57-inch wheelbase.

One of the Paso’s engine changes was that the head of the vertical rear

cylinder was turned 180 degrees to adopt a more rational central induction

system. Doing this got rid of the additional cables and unequal throttle

response from the traditional Dell’Orto PHF-PHM carbs. In their place was a

Weber 44 DCNF automotive-type twin-choke carburetor. The Weber not only returned

smoother and had more precise throttle response, but it also improved the torque

delivery, moving the 65 hp power peak (net, rear wheel) down from 8,800 to 7,900

rpm. The Weber’s drawback came due to the fully enclosed fairing: In slow

traffic, the fuel in the bowl would overheat, and the engine would lose

tractability and finally die because there simply wasn’t enough cooling airflow.

Paso

The Paso featured a modern and elegant instrumentation cluster. Clip-ons placed

atop the upper triple clamp induced a streamlined and sporty but very

comfortable riding position.Bruno dePrato

The problem remained even when the old faithful air-cooled 750cc SOHC was replaced by the liquid-cooled 904cc SOHC unit based on the 851 eight-valve Desmo crankcase, complete with the new six-speed gearbox. Named the Paso 906, it represented a sound evolution of the original, since the chassis was more than capable of dealing with the 74 hp peak power at 8,000 rpm and stronger torque of the larger unit. The Paso 906 was much more versatile than the 750, and fast, strong, and handling well, it was a great pleasure to ride anywhere. Top speed easily exceeded 135 mph, finally delivering what the sleek lines of the fairing promised.

When it came time to adopt a new, fuel-injected version of the 904cc unit, Ducati decided to homologate a new chassis and switch to 17-inch wheels, which were then coming into fashion. It was a bad idea, hastily put together and completely overlooking the fact that the wheels and tire sizes were a determinant factor in chassis balance. Using a 120/70-17 front and 170/60-17 rear completely trashed the original dynamic quality of the Paso project. The Paso 907 i.e. was forced to grow taller, not only because of the larger diameter of the wheels and tires at both ends, but also because the front wheel demanded a much taller fork to push the larger front wheel forward in order to clear the front cylinder head. Wheelbase grew by nearly 1.6 inches, and the Paso lost its light, precise steering, and became heavily understeering like other Ducatis of the time.

The only positive brought by the Paso 907 i.e. was its fuel injection, which added a little power (now 78 hp at 8,500 rpm) and completely eliminated carburetion problems. Still, it was the sad swan song of a great project while it should have been the cornerstone on which the Ducati technical team could have built a new competence in motorcycling dynamics. But by then, Tamburini was actively working on his perfect Ducati 916 jewel. Godspeed Massimo. Always.

Source cycleworld.com

Road Test

The Ducati 90-degree V-twin we've come to know and love and have watched win Daytona has a new twist; it's called a Weber.

But if you remember the October test report on the prototype Paso, you know there was more than red paint to attract us. After all, Honda Rebels come in red but don't affect us the same way. Would the production Paso retain the streetability of the prototype? With bursting lungs we climbed aboard the Paso that Cagiva North America delivered to our office on a brilliant winter afternoon. The Paso comes in black or red; guess which color we requested.

The full bodywork gives the impression of a carved piece of wood or bubble of blown glass with its smooth, compact shape. The bike appears low and squat, and that feeling stays with you when you're planted in the long, red saddle. The reach to the buffed aluminum handlebars isn't the long stretch to the Ducati F-1's low clip-ons, and combined with the rearward but civilly low foot-pegs, the riding position is unquestionably comfortable, a la RG500 Gamma. The wind flowing over the solid fiberglass windscreen area helps prop the rider in position and hits him high on the chest. The production version has a slightly more curved screen area that tallies even more style points than the prototype. We say "windscreen area" because it is solid painted fiberglass, a direct extension of the bodywork, not a transparent plastic windshield.

Missing from the prototype, but necessary in the modern world, were mirrors and turn signals. Where do you graft signals and mirrors on bodywork this exquisite? Ducati cut the problem in half by making the front signals and mirrors one and the same. The turn signal/mirror pods snap onto the lower section of the fairing uppers, much like on the BMW K100RS. This places the mirrors quite low, even lower than the handlebars, and adjusting to the new mirror position takes a few blocks. In the four-inch, round mirrors the rider sees a little bit of his leg, and beyond that, the road and any cars on it in surprising clarity. Our testers noted that to use the low mirrors, the rider had to take his eyes off the road for a little longer than was comfortable, and direct rearward viewing necessitated a slight change of rider position. The Ducati stylists and test riders each achieved victory; the mirrors fit the Paso perfectly and work better than mirrors on several current Japanese sport bikes, notably the FZ600 and Ninja series.

The rear turn signals will be revised to American specifications on the Pasos delivered to dealers because they are now too close together to suit our Department of Transportation. Look for the flush-mounted rear shiners to be replaced by uglier, but legal, stalk signals.

The details of the Paso add a great deal to the whole package. For instance, the switches are the best yet on an Italian bike. The turn signal is push-to-cancel, something Kawasaki can't seem to provide on its sport bikes, and the lights, starter and on/off switch are functionally straightforward. Our early production model was rushed to the U.S. with the European high-beam flasher switch still in place; later models will have the same excellent switch gear, minus the passing switch.

While the initial impression of the Paso is awe-inspiring, a pretty face won't sustain a motorcycle. What exactly is behind the Paso's pretty face, and does it sustain this motorcycle? Close inspection of both the details and the main components gives us the answer: functionally as well as aesthetically, the Paso can look any sport bike in the headlight without flinching. For a first-year bike, the Paso has amazingly few rough edges.

The Ducati 90-degree V-twin we've come to know and love and have watched win Daytona has a new twist, and it's called a Weber. The twin Dell'Or-tos are gone, the rear cylinder head has been spun around 180 degrees and a dual-throat Weber carburetor plonked down in the V. Gone with the Dell'Ortos is the stiff throttle pull no rider will miss, and other than a slight lean stumble just off idle, the carburetion is glitchless and our forearms are now crampless—a wonderful trade. Another Weber benefit is its simple and infinite adjustability; Weber hasn't remained in the carb business for decades because of dumb luck.

The frame engulfs the engine. From the steering stem, a cradle of two rectangular steel frame tubes drops down and under the engine, meeting with a second set of rails that span the gap from the steering stem to the swingarm axle in the straightest path possible. Both these rectangular sections brace the bottom of the steering stem and a third member extends from the top of the steering stem to halfway down the top frame rail. For the seat and tail-section support, smaller rectangular steel frame members are welded on the main unit, forming triangles from the main frame to the rear of the bike. None of this is particularly lightweight or cutting-edge technology, but the welds are neat, the frame rigid and successful. A frame is successful if it doesn't flex under hard sport riding. The Paso frame doesn't flex detectably. We spent a lot of time making sure.

Welded to the frame are all manner of brackets. Brackets to hold the coils, the electric fuel pump and the small sub-frame reaching ahead of the steering stem that supports the wide headlight and gauges. Under the prototype's bodywork, the brackets, fittings and hoses looked rough, a few didn't work well and a few were missing. All that has been corrected on the production version, and the details have been developed to improve the Paso's underbody function and looks. The dual oil coolers now slide into the fairing lowers on beds of dense foam rather than rely on the rubber straps of the prototype; details such as the oil hoses and thermostat wiring on the right cooler have been updated.

The word details keeps appearing in this test. From the quality of the bar switches to the finish of the welds and tabs, the Paso sets new detailing standards for Ducati. The Cagiva buyout of Ducati has brought updated quality standards. This motorcycle was almost titled the Cagiva Paso until Cagiva's president, Gianfranco Castiglioni, had a change of heart and decided to use the Ducati name. If you've been noticing Cagiva's products over the past two years, you know the company is serious about making motorcycles that compete head on with current (read Japanese) bikes. The Paso is one more big step in that direction.

A few items on the Paso need a little work, however. The bright red seat on our bike matches the Paso's paint well but doesn't fit flush with the tailpiece there's a half-inch gap when the seat is locked in place. In direct sunlight a few of the dash lights are unreadable, such as the turn-signal indicator. At night the red dash lighting makes it difficult to read the clock and gauges, which have red numbers and lines. We had to trace down a faulty electrical connection in the fairing that was causing the lights to flicker on and off. We'd also like a grab rail on the left side under the passenger seat so we can more easily hoist the Paso on its centerstand. A matching rail on the right would provide a bungee-cord fastening point.

The seat-bar-peg combination, which staffers rated between comfortable and terrific, is complemented by the well-thought-out suspension. Each end has approximately five and a half inches of wheel travel, and the suspension units are top-rate and highly adjustable. In back, an Öhlins shock rides in Cagiva's Soft-Damp forged alloy progressive linkage. With adjustable spring preload, rebound damping and compression damping, we could dial in any ride characteristics we wanted. From the company that brought us the buckboard ride of the F-1 comes one of the smoothest-riding sport bikes we've tried. Apparently, the Cagiva-Ducati engineers discovered what the Suzuki GSXR designers know about sport-bike suspensions. The lighter preload settings gave away a little Ground Clearance, but after we made some adjustments under the left side cover to firm the ride, the ground-clearance problems vanished. Two alien bolts hold the side cover, and the alien wrench is under the seat in the tool kit.

As the inscription on the fork proudly announces, it's Marzocchi's best, the M1R. And again, there are plenty of adjustments. The right leg handles the rebound-damping chore with an external adjuster knob we mistook for anti-dive when we first spotted it. Compression damping is the left leg's responsibility, and if the rider wants it changed, he must change the fork oil—but only in one leg. Air valves hide under rubber spin-off caps at the top of each leg. The M1R complements the rear Öhlins wonderfully. Both systems keep the tires firmly i

from highway expansion joints to braking ripples on a racetrack, and their progressive action allowed our testers to run comfortably compliant settings, but the Paso never felt undersuspended.

The Paso isn't a snap-steerer like the FZ600 or the Bimota db1. At 57.2 from axle to axle, the Paso is medium long, and although 25 degrees of rake and 4.13 inches of trail seem like quick numbers, the longish wheelbase that comes with Ducati's engine layout keeps the steering in the human realm. The 492-pound wet weight, with the 5.9-gallon gas tank full, must also be plugged into the equation. Frankly, we expected the bike to weigh in at around 450 pounds. The minuscule db1 is three inches shorter and weighs 85 pounds less than the Paso, but no testers complained that the Ducati felt heavy. Regardless of the weight, the Paso responds sharply and crisply to steering inputs but not with the alacrity of the above-mentioned bikes.

The wide, squat 16-inch Pirelli MP7-S radial tires have a big effect on the Paso's steering. Initial turning takes a relatively light push or pull on the handlebars, but as the tires roll up on the wide, flat outer contact patches, they begin to resist the turning force. More counter-steering force must be applied to continue to lean the Paso the extra few degrees onto the cornering patches of the Pirellis. Looking at the frayed tires after the test rides, you realize this characteristic didn't bother any of our testers. It just takes a little adjustment in steering pressure at the handlebar. The flip side to the wide Pirellis' handling traits is their wide contact patch and impressive traction under braking and cornering loads. These suckers stick. Our corner entrances and exits were full brakes to full throttle because the radials refused to slide or misbehave in any way. They are quite soft, however, so plan on replacing them fairly frequently; that's the price of premium rubber.

As we noted in the initial test of the prototype Paso, the wide 130/60 front radial wants to stand the bike up if the front brake is applied while leaned over. The monstrous 160/60 rear radial adds to this tendency. More common than braking in a corner is running into the corner with the front brake on. The wide tires force the rider to increase his pressure at the bar to initiate the turn with the brakes on. This tendency isn't as pronounced on the Paso as on the DB1. The Bimota has much stiffer suspension, which makes the frame react more quickly to any braking force. Again, our testers noted this tendency but, to a man, feel it can be easily adjusted to.

Nothing about the engine's performance takes acclimation. The power is as seamless as the paint on the fairing and potent enough to whip the Paso through the quarter-mile in 12.89 seconds at 103.3 mph, corrected for altitude and weather. In our 50-mph roll-on the Ducati reached 74.9 mph after 200 yards, compared to 72.8 for the F-1 and 79.1 for the strong Alazzurra 650.

The Paso version of the familiar des-mo utilizes a larger oil pump to keep the slippery stuff pumping through the two fairing-mounted coolers, and the right clutch cover hides a hydraulically operated dry clutch that hasn't given us a peep of trouble. The air-cooled twin, in either production or prototype form, never hinted at overheating even in stop-and-go traffic on hot days running on regular unleaded fuel.

Ducati claims 52 foot-pounds of torque at 7000 rpm, with a maximum claimed output of 75 horsepower at the 9000-rpm redline. Our testers found no point in habitually spinning the desmo to redline because the midrange power is so usably abundant and the power levels off above 7500 anyway. The throttle takes a full half twist until the Weber is

WFO, and the last few sixteenths of an inch of throttle make a big difference. At full throttle the sound reaches its zenith, the slight intake honk meshing with the dual mufflers' shout.

We can thank the full bodywork for the Paso's exhaust music because the engine's noise is effectively muted, allowing the exhaust to flow more freely, or loudly, and still sneak under the U.S. standard. It's interesting that we can thank the red full-wrap plastic and fiberglass body for more than simply putting our hearts on overrun. The body gives the Ducati desmodromic V-twin a second lease on life; the front half of the huge fuel tank masks the Weber's airbox and the bodywork saves us, the consumers, money on the Paso's retail price. An encompassing body allows the engineers to skip the expensive and time-consuming job of finishing the engine case bolts, routing the hoses out of sight or hiding items such as the coils, fuel pump or turn-signal flasher. All these necessary items can be bolted on where they fit, then covered with ABS and fiberglass—clean, neat and intelligent. We hoped the full-coverage body would help keep the price under $6000, but the price is set at $6377. That's high for a 750, but we're betting Cagiva will sell every Paso imported. It shouldn't be hard—just 700 units are slated for the U.S. market in '87.

Source Motorcyclist 1986

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |