|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

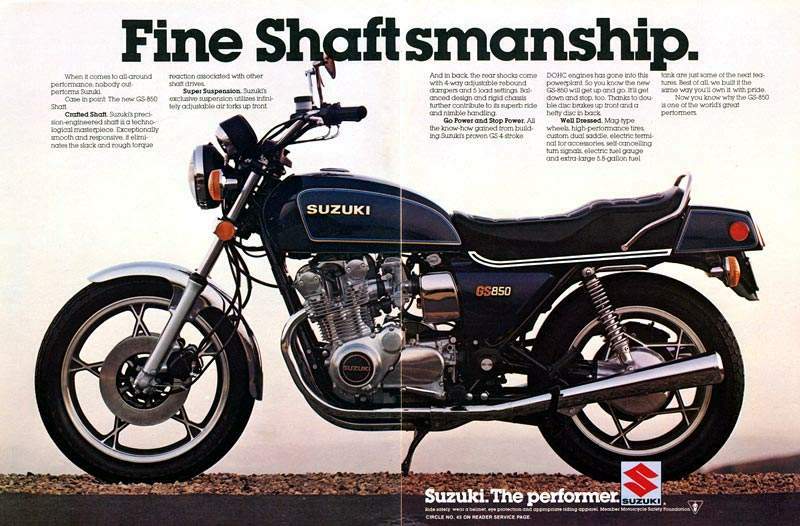

Suzuki GS 850G

The 850cc versions of the GSX750E was available only with a shaft drive and were

called GS850G.

GS850G was introduced in February 1979 with a 5-speed

gearbox, twin front and single rear disc brakes, 19-inch front and 17-inch rear

alloy wheels. It had a fuel meter, automatic turning indicators (returning after

ten seconds), both electric and kick start and a shaft drive. The test team also praised the suspension and the seat of the GS850. Although it had a smooth, vibration-free engine it needed to be ridden at 5.000 rpm and above with heavy load — after all it had only 77 horses. The team didn't like the handlebar (too narrow for such a heavy bike) and the placing of the footrests (too high and too far ahead). ”Harmonic and easy to handle, both on road and streets.”

Road Test

PLENTY. OF THE MOTORCYCLES WE TEST are good enough, on balance, to be worthy ot the famous (and mythical) Cycle Seal of Approval. Suzuki's new GS850. by virtue of conspicuous merit displayed in all the standard categories of evaluation, easily earns the Seal—with laurel clusters, which is an award our jaded test riders bestow on a motorcycle they judge to be simply, totally and supremely nice. Not the fastest thing on two wheels; not absolutely the best handling; not the most comfortable. Just perfectly nice, in ways that make you want to ride when the weather report says you shouldn't and leave you with a warming residue of regret long after the days of riding are done. You may be thinking, as we did, that Suzuki should have developed the GS850 from the GS1000 instead of basing it on the GS750. Shaft-drive machines do carry more weight than their chain-gang brethren and the lighter, more muscular, larger-displacement engine would seem to have been a better starting point. Suzuki had good reasons for the choice they made. One was that many insurance actuaries recoil in horror from all motorcycles with engine displacements above 900 cubic centimeters, especially those owned by young men Viewed in that light Suzukis decision to stretch the GS750 makes sense. There's more than the expense of manufacturing in the ultimate cost of motorcycle ownership, and Suzuki didn't want to price the new shaftie beyond the typical young man's reach. Another reason for using the GS750. rather than the newer GS1000. was that when the decision had to be made, the latter was still very new. White the 1000 looked good in pre-production testing and while there was no reason to doubt the 1000's reliability, the GS750 had been in service long enough to have absolutely proven itself. Further, the GS750 engine actually was—and is—stronger. Suzuki's engineers pared weight out of the GS1000 in hundreds of small slices, taking it even from the main bearing supports and crank cheeks. They now know the paring wasn't overdone, but that hadn't been demonstrated back when the shaft-drive project was begun. The GS850's engine basically is a 750 with bigger (69 millimeters versus 65mm) pistons. Its cams were borrowed from the GS1000, which also provided the 850's helical-cut primary gears. Suzuki nudged the displacement upward to compensate for the effects of an anticipated weight increase and opted for the helical clutch-drive gearing because that's quieter and stronger than a set of straight-cut cogs of the same diameter and width. Apart from the pistons and cams, no engine changes were made and we have no complaints about that. When you already have a substantially state-of-the-art DOHC engine, there's little reason for major changes to be made. Suzuki's creative urges obviously did find an outlet when the GS850's final-drive layout was being designed. The problem is to turn the drive 90 degrees behind the transmission and direct it back to a BMW-esque gear housing at the rear wheel hub. And to provide a drive-shock cushion to protect the whole drive tram, which will be more tightly tied together than it is when a chain and sprockets aro used. Others have resorted to transfer shafts and gears behind the transmission and/or separate bevel gear housings. But Suzuki grafted the necessary additions onto their existing shafts, taking advantage of available width and holding to the bare minimum the number of gears involved in transmitting power to the wheel. To do all this. Suzuki enlarged the bore in the hollow transmission input (forward) shaft and replaced the clutch release rod with a long, slender drive shaft connecting the clutch hub and the spring-loaded dnve cushion. (A pull-type clutch release replaces the pushrod mechanism used in the GS750.) Power feeds from the inboard end of the drive cushion straight into the transmission's input shaft, where it is routed across the gears in conventional fashion to (he output shaft and. via a shod extension, to the bevel gears. The bevels are placed about where the GS750 has a sprocket but are within the widened transmission cases. It must be stressed here that the width we're talking about is just dead space behind decorative covers in the chain-drive Suzukis; there has been no increase in the distance the rider has to straddle with his feet. Indeed, the only obvious external difference between the GS750 and GS850 is that the tetter's rear transmission wall is blank instead of having a chain cavity. Nothing shows outside but the flanged attachment for the drive shaft's U-joint. which is of the conventional automotive "Hooke" type rather than the more expensive constant-velocity coupling. Suzuki's choice of U-jomts may partly account for the elaborate system of elastic couplings in the drive train. The angular displacement of the Hooke-type joint's yoke produces cyclic speed changes In the rotating shaft, when the joint is working at an angle, and this can generate a torsional vibration. Suzuki may have had that in mind when the GS850 was given rubber-loaded bushings between its final drive gears and rear wheel, a spring-loaded face-cam cushion between clutch and transmission, and the usual set of shock-cushioning springs in the clutch itself. The arrangement works: there is no appreciable transmission-related vibra-tion-and very little of the drive-train lash we have all come to know and loathe in certain other motorcycles, mostly Yamahas in this regard.

Another point at which the GS850 is a lot better than most Japanese-made machines is its shifting action. Any of the present generation of motorcycles will stir their gears in reasonably orderly fashion if you apply a firm toe at the change lever The Suzuki needs nothing but a light dab and snicks from one gear to another so smoothly its rider has to get really sloppy to miss shifts. This is one of the little things that makes the GS850 such a pleasure to ride. We like the shift action so well we're almost willing to approve of Suzuki's trendy digital gear indicator lights, which display in bright red numbers the gear you've engaged. These numbers used to be formed by LEDs (Light Emitting Diodes) but Suzuki has switched to regular fitment-type bulbs behind red-tinted glass. The neutral indicator is still a green light, and it's still easier to get the bulb glowing than it is to actually get the transmission into neutral after the bike has stopped. It's easy to predict which ot the gear indicator light bulbs will be the first to burn out. Somehow, perhaps with the added displacement and GS1000 cams, Suzuki has made the 750 engine into a solid low-speed lugger in the GS850. We still haven't devised a satisfactory means of hooking shaft-drive motorcycles to the Webco dynamometer, so we can't tell you with scientific certainty where the GS850's useful power begins. But the engine feels like it's ready for serious business at any crank speed from idle to the 9000-rpm redline.So. unless you want to do some shifting just for fun, you can short-shift your way to fifth and forget the lever is there. Top gear will take care of all speeds down to about 25 mph; the GS850 needs shifting only when you want speed in a hurry. One of the more amazing things about the GS850 is that it is able to gather up a hurry when you want one. The bike is not only heavy for an 850, but heavy in the absolute sense. Top up its tank with fuel and it registers just over 600 pounds on a certified scale. Yet the GS850 ran through the speed lights during our quarter-mile testing at 104.77 mph, which is motoring right along. Its weight showed only in the relatively slow elapsed time, a wink under 13 seconds, which reflected a sluggishness during the first 20 feet more than any reluctance about gathering speed once it was truly moving. We know a 600-pound 850 shouldn't have Superbike acceleration, especially when it's pulling tali gearing, but the GS850 does. It's only about as fast as a good 500 getting across the tirst halt ot an intersection, but from there on it feels like a 1000. The GS850's suspension is a mixture of GS750 and GS1000 hardware. Its fork differs from that on the 750 only in having tubes that are 20mm longer, and the springs and air valves come directly from the GS1000. The rear shocks, which have four-stage adjustable rebound damping, are from the 1000 but carry different coil springs. Suzuki does not supply the pump and air gauge you sometimes get with a GS1000 to set the GS850's air-fork pressures. They provide a dial-type air gauge and instructions about how much pressure you should use in the fork tubes. They should include their very best wishes because that's the least you'll need when you arrive at a service station ready to put some more air in the fork. We found that adjusting the fork air pressure was a very difficult job without the GS1000 tool. It's easy to get the caps off the little valve stems (our test bike lost all its pressure when ridden with the caps off) and you don't need a special air chuck. But the quickest jab with the chuck we could manage put the pressure at 30 pounds per square inch and on most tries we sent it beyond the gauge's 40 psi scale. We then learned to just tap at the valve stem to bleed off pressure—and found that each quick tap was worth a four psi pressure drop. We also discovered that merely checking the pressure with the gauge reduced the pressure by about two psi. It wasn't easy to fiddle the pressure where we wanted it. The only reason this adjustment won't be a big problem for GS850 owners is that they won't have to do it otten. For all practical purposes, it's purely a ride-height adjustment. Owners will lind it useful in compensating tor the weight ot a big windshield fairing, and the spring-sag that comes with many mites of riding. We found no difference in ride with fork pressures varied between zero and 30 psi. and onty small variations in handling (at cornering speeds somewhat more lurid than the sane motorcyclist would enjoy). Rear suspension adjustments were easier and produced larger differences. The usual adjustable lower spring collar is there and. as usual, it sets only the bike's rear ride height. You crank up preload if you're going to carry a passenger or it you want more cornering clearance. The other, less familiar adjustment is in the shocks' rebound damping; this one is made by turning the knurled collars under the rubber weather boots just below the upper shock eyes. And on some surfaces there is no perceptible difference between "1" (the softest setting) and "4" (full-resistance). One stretch ot nde-quai-ity test road we use has a wavy surface, with about 10 feet between crests and a couple of inches from crest to trough. On that road the GS850's ride did not change when we ran Ihrough the range of damper settings. And the ride was good. Those undulations send most motorcycles into a fierce hobby-horse pitching when traveled at 50 mph; the GS850 only nodded going across them. The damper adjustment did make a difference on choppy surfaces (i.e. cracked, patched and pitted pavement) and in the GS850's cornering behavior. Specifically, the higher-number settings felt like compression damping stiffness. Apparently, lots of sharp ripples cause the dampers to pump down, effectively stiffening the springs and making the suspension more harsh. This effect was felt when cruising along, riding solo, on rough roads, and it made the GS850 chattery when cornering fast on smooth surfaces. Both conditions disappeared when the damper resistance was reduced. In truth, you can't really fault the GS850's handling. We noted a little fork stiction-retated front suspension harshness, which might well have been correctable by loosening and retightening the axle clamps, but that had no influence in cornering. With its fork pressurized to 15 psi and its rear damping at "2" the Suzuki was as near perfection as a 600-pound motorcycle is likely to be anytime soon. Its steenng is absolutely neutral, and the motorcycle is both agile and astonishingly steady after you've levered il into a turn. The IRC "Grand High Speed" tires seem to cope wilh the load extremely well, and only the intimidating thought of what it might be like to wrestle 600 pounds of sliding motorcycle acts to keep one's enthusiasm in check. You just know that if so much mass gets out of control, it's going to stay beyond control a long, exciting time. Otherwise.the GS850 will let you play canyon-racer all you like, or at least as much as you think you can get away with. The GS850 doesn't (perhaps due to its sheer weight) display the typical shaft-drive bike's power-on/power-off attitude. The refined suspension components aside, a lot of the GS850's excellent road manners have their foundations in the frame and attachments Suzuki has provided. Suzuki clearly has come to treat frame rigidity seriously, They use stout tubing and plenty of gussets and struts, and the GS850 says the approach is working splendidly. Suzuki also has switched to tapered-roller steering-stem bearings, which are free from the pitting that has begun to afflict the overloaded ball bearings still occasionally used in big bikes. Tapered rollers' greater capacity for withstanding abuse make them a good—if expensive—choice. The GS850 has them at its steering stem, and the swing arm pivots on them also. Evaluation of braking performance has been changed by the introduction of hydraulics and discs into motorcycling. Back in the bad old days of drum-braked big bikes, stopping power was a sometime thing. But sheer braking force almost never is lacking with discs, especially when-as is the case with the GS850-you have a dual-front, all-disc system. So you think in terms of controllability, the tire/road connection, and whether the chassis can take heavy braking loads without flexing completely out of alignment. The Suzuki had impressive scores in all three categories: its brakes are smooth, powerful and precise; the tires do their job better than the GS850's weight should allow; and the chassis doesn't develop any ideas of its own. The importance of total controllability under mixed braking and cornering should not be underestimated. For some riders it's part of their style, but for anyone who allows sporting spirit to lead him in harm's way (and into a turn that proves tighter than it looked) it becomes a like-it-or-not necessity. Cycle's test riders, to their shame and occasional sorrow, get themselves into such predicaments rather often, and some of their affection for the GS850 comes from its willingness to combine vigorous braking and turning. Source Cycle magazine 1979

|

|

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |