|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

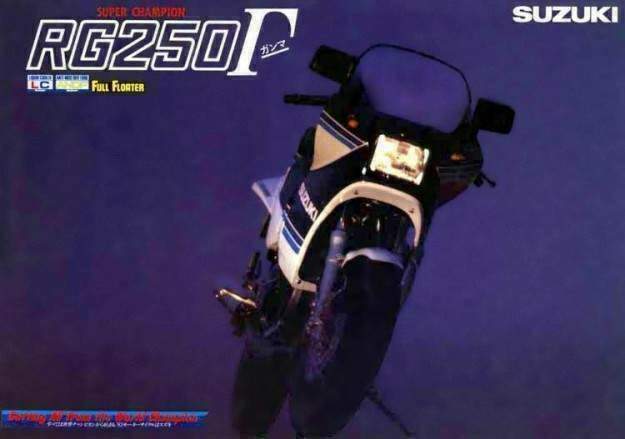

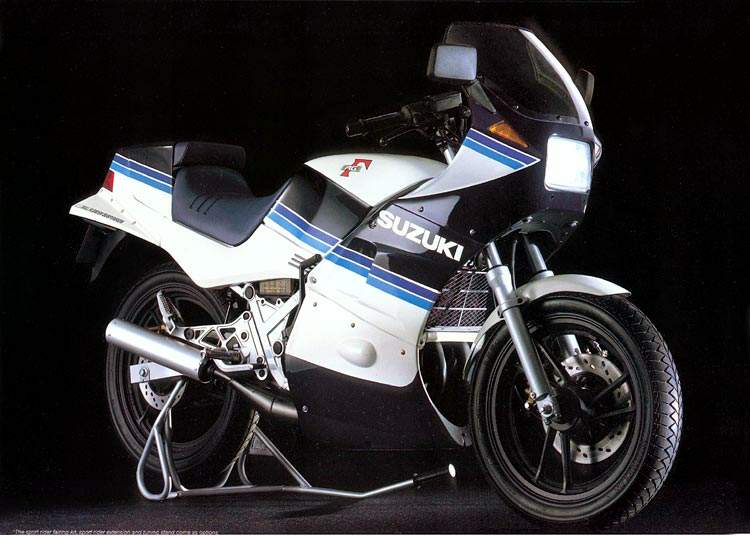

Suzuki RG 250 Gamma

|

| . |

|

Model. |

Suzuki RG 250 Gamma |

|

Year |

1983 |

|

Engine |

Two stroke, parallel twin, reed valve |

|

Capacity |

247 cc / 15.1 cu in |

| Bore x Stroke | 54 x 54 mm |

| Compression Ratio | 7.4 :1 |

| Cooling System | Liquid cooled |

|

Induction |

2 x Mikuni VM28SS flat side carburetors |

|

Ignition |

Pointless Electrical Ignition |

|

Battery |

12V, 5Ah |

|

Starting |

Kick |

|

Max Power |

32.8 kW / 45 hp @ 8500 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

37 Nm / 3.8 kgf-m / 27.3 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm |

|

Clutch |

Wet, multi-plate |

|

Transmission |

6 Speed, constant mesh |

|

Final Drive |

Chain, #520, 110 links, O-ring sealed |

|

Front Suspension |

Telescopic fork, coil spring, oil dampened with anti-dive |

|

Front Wheel Travel |

130 mm / 5.1 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Full Floater, mono-shock, gas/oil damped, spring preload fully adjustable |

|

Rear Wheel Travel |

122 mm / 4.8 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2 x 260 mm Discs ,1 piston caliper |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 210 mm disc, 1 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

100/90-16 |

|

Rear Tyre |

100/80-18 |

|

Rake |

24.7o |

|

Trail |

102 mm / 4.0 in |

|

Dimensions |

Length: 2050 mm / 80.7 in Width: 685 mm / 27.0 in Height: 1220 mm / 48.0 in |

|

Wheelbase |

1385 mm / 54.5 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

155 mm / 6.1 in |

|

Seat Height |

785 mm / 30.9 in |

|

Dry Weight |

131 kg / 289 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

17 Litres / 4.5 US gal / 3.7 Imp gal |

|

Oil Capacity |

1.2 Litres / 1.3 US qt / 1.1 Imp qt |

|

Consumption Average |

6.6 L/100 km / 15.2 km/l / 35.7 US mpg / 42.9 Imp mpg |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

14.4 sec / 145 km/h / 90 mph |

| . |

The arrival of the RG250 represented a new phase of Japanese engineering. It was, of course, quicker than the RD250LC, in fact it was just about as fast as the RD350LC (and it cost nearly as much, too). But there was more to it than that.

It was functional, using the extra stiffnes of box-section alloy instead of thinner-walled steel tubing and an engine which was, necessarily, peaky in order to achieve its performance.

It had good suspension, which worked very well despite the relatively low weight of the bike and it had a high build quality with lots of neat touches and well-made parts which made it nice to look at, nice to sit on and satisfying to use. Much of this was rare in any roadster. On a 250 it was unique. The later mark 2 and mark 3 models smoothed out some of the peakiness and grew a very stylish full fairing. The Gammas opened up a whole avenue of production racing, gave the Yamaha-based tuning fiops a hard time and founded a new industry supplying cheap aftermarket bodywork which production racers could afford to crash.

Its cost was out of line with its capacity, but so was its performance, and nobody seemed to mind. People did mind the precarious sidestand and the pitiful tank range — usually less than 100 miles when used as intended.

Review

Pull the engine revs up near the power peak as you feed the clutch in. Remember, off idle this thing has about enough power to blow you a kiss from two paces. Rev, then slide the clutch through most of first gear to keep the engine pulling strong. For a Bonnie and Clyde blast-off, be careful. Don't let those revs fall too far, or else the engine's power will go out like a light, delaying your launch. Unacceptable! Keep that tach needle flashing above 5000.

On a straight piece of road, you're almost violating the 9000-redline in fifth gear. A tight, 90-degree left-hander pops up on the horizon. Full attention, please. Apply binders. You get the brakes on hard as the turn closes in on the Gamma. You can't be clumsy with the rear brake; it rewards the heavy-footed by locking up. The superb front brakes, sticky tires and forward-mounted engine set the Gamma's behaviour terms under forceful braking. Since weight seems to transfer to a point under the front axle, you just touch the rear brake pedal. Elevating the rear tire under hard braking is neither unthinkable nor impossible. Watch for mono-wheeling, front-end style.

Here's the corner, now. Ease off the brakes slightly just as you toss the Gamma in to the left. Pitch decisively, but be smooth. Too much front brake during the turn-in and the light rear end will momentarily feel as if it's on a side excursion. Ragged riding at this crucial moment will have you cultivating in the roadside ditch.

This Gamma game room has a ceiling about 2000 rpm above its floor. Levitate in this space by dancing with the gear shift lever. Be in the right gear at the right time, and you'll be okay. Screw up - and you're on the floor.

Don't forget where this arcade game is going, either, right through the apex of a corner.

Get back on the power when positive messages come up from the tires, and let the bike arc toward the outside of the pavement as you reach full throttle. Now snick/snick, third/fourth, before you nick the close-ratio six-speed back for an instant to enter the second turn, an 80-mph right-hand sweeper, a corner where momentum is the key. It exits onto a lengthy sixth-gear straight.

After you swoop through the right, tuck in while the tach needle waivers at redline in top gear. Be alert. It's time to dive back through the gears and brake for a left-right-left multi-speed combination. Don't be too aggressive; the rear wheel has to stay on the surface. The first left is a fourth-gear sweeper which dumps into a third-gear right. Quick, cooperative steering is mandatory on this left-right combo: because the brakes are on all the way from the entrance to the left until you peel off for the right. The 16-inch front wheel eases the effort to get the hard-worked front tire to do what it must - turn-brake-stick.

The Gamma does the left-right flip with a touch of "top-side." For a fleeting instant the bike gets feathery when it's un-weighted during the transition, a trait shared by all lightweight, race-bred machines. Nothing to get excited about. It just registers in the pit of your stomach. Concentrate. Exit the third-gear left. Hey, nice combination. Nice bike. Oops. Stay to the right for the approaching second-gear left-hand hairpin; set up for a late apex, because you'll get the maximum drive down the following long straight. Brakes. Careful. Pitch. In and out. Neat! Getting through these corners like a beam of light reflected from mirror to mirror is the key to finishing first at the end of the, at the end of the, well, road.

Road? The hell you say. Yes, that's right, road, and on a street bike no less. One complete with lights, turn indicators, battery, horn and license plate. The messages sent up from the bike, the feedback from its aggressive, surefooted, responsive manner speaks racetrack. But you're out there laughing at those other poor fools who are yanking on lumbering, everyman motorcycles. What an embarrassment you are for them with this 250. If they only knew. They've been working with cannons. You've had a ray gun.

It's doubly embarrassing to them when they realize the bike you're riding is only a 250. Suzuki's RG-Gamma does more than share a name; it carries the repli-racer connection beyond that of any other street-runner ever tried by Cycle. It doesn't merely look like the World Championship-winning model; it is, in many respects, the same. Never mind-that it only displaces 250cc or makes a modest 30 horsepower at the rear wheel. This 250 is Gamma-like because as it goes down the highway it responds to rider commands with the same kind of directness that its namesake, the RG500 Gamma, would on the racetrack. Never before has a motorcycle been so successful echoing the latest war whoop from the Grand Prix circuits.

Look at this pint-sized Gamma. You've seen it before at places like Imola, Nurburgring and Silverstone. Lots of today's sport bikes have square-section frames, but they're mild steel stuff. Now ask yourself what factory ever raced one made of steel. Exactly none. And how many street bikes have you seen with aluminum frames? None, unless you take the time to look at the RG250 Gamma.

Suzuki has made the Gamma's entire chassis from aluminum, from the fairing mounting tabs welded to the steering head to the seat brackets at the rear. All the welds on the RG, whether easily visible or not, look like the work of a Michelangelo of torch and rod. These Suzuki guys actually mass-produce these things. Though its construction bears many similarities with its championship-winning brother, concessions to production-line practicalities do exist.

In those areas where the swing arm and Full Floater suspension anchor, the RG500 race-bike frame is built up from aluminum plate and hollow extrusions welded together; the 250 Gamma uses die-cast aluminum plates welded in place. The die-castings, which also serve as the mounting points for the footpeg/muffler carrier, are not solid, inch-thick plates as they appear. Their backsides are hollow with stress-carrying ribs. Light and strong, these castings are labor saving devices for the chassis builders. They're also gorgeous. Any extras for ashtrays?

The RG's steering-head angle is a steep 24.7 degrees, the four inches of trail middle of the road. The steep rake follows current racing design practice. On the racetrack, where a rider must be able to change the motorcycle's direction at the speed of thought (or faster), steep rake angles are mandatory. The four inches of trail is more than an engineer might use on a racer, but on a street bike it's necessary because normal riders should have a lot of self-contained, built-in high-speed stability. Race riders learn to cope.

On the 250 Gamma, front and rear suspension are well balanced, though both seem a trifle light on rebound damping near suspension top-out. Suzuki has already adapted the GP-Gamma's Full Floater system on many new models, street and off-road. The company has the single-shock rear system down pat on the Gamma 250, and it matches up to the fork, a 36-millimeter, 5.1-inch travel unit with Suzuki's ANDF (Anti Nose Dive Fork) system. A steel fork brace, concealed beneath the front fender, adds more rigidity. On the 250, braided stainless steel lines connect the brake calipers to the ANDF activating pistons. These lines don't flex, and as a result, the front brake lever vagueness, so characteristic of many ANDF Suzukis, has been reduced.

With the exception of the shock, the superb Full Floater uses almost entirely aluminum sheet and forgings. The effective suspension suits perfectly the abuse the RG250 invites—busting down backroads as fast as the rider and motorcycle can go, GP style. A remote preload adjustment knob located below the side-cover aids preload tuning, but the engineering department left no provision for adjusting either compression or rebound damping. Rear suspension travel measures a moderate 4.8 inches, but in light of the rather quick front-end geometry, that's probably a good thing. Were road surfaces bad enough and speeds sufficient, great deflections with long-travel suspension might upset the bike's geometry, and the rider would receive a wobble-message telegraphed to the handlebar.

The gold-finished dual-piston brake calipers are the same excellent units fitted to the 1983 GS550ES series. The front brake system, apparently a direct carry-over (minus a little black paint), ranks among the best of the Japanese OEM stoppers. Your imagination probably can't do the stopping force of these brakes justice when they're cinched on the Gamma. Five-fifty owners, put this in your files—the Gamma weighs 140 pounds less than a GS550. The rear caliper-rotor combination is a .250-Gamma exclusive. Considering the front brake's phenomenal power, the rear brake has a light work load, not that you'd want a highly excitable brake on a wheel that can get airborne under heavy-duty braking anyway. The small brake rotor saves considerable weight in a place where it really counts. Comparatively, front/rear brake size is yet another similarity between the deadly-serious 500 GP and the all-for-fun 250. Those product planners in Hamamatsu knew what the world's street demons would be doing with the little Gamma.

Down in the engine bay, the similarities between the real and the road Gammas end. Building a 250cc version of the disc-valve 500 square-four would have been outrageously expensive and stupid. Suzuki would have had to mortgage their General Motors stock to have done it, and were it done, the engine would be a 500. There's nothing too fancy in the RG250 Gamma's parallel twin. The 54 x 54 Gamma has bore and stroke dimensions identical to the latest production 125cc motocross engine, and the RG utilizes Suzuki's Power Reed (case reed) intake system. A pair of equalized 28-millimeter flat-slide Mikuni carburetors feed the cylinders and draw air from a huge airbox fitted with an oiled foam element.

Since the Gamma is a small bike with a single-shock rear suspension, components like the airbox and battery must be herded carefully into existing space. We'll bet the engineers who managed to get 10 pounds of components into a five-pound hole ride up and down 10-man elevators in packs of 15.

The one-piece cylinder head with its integrated thermostat housing has squish-band combustion chambers.

Compression ratio is 7.1:1. Below the head, the individual iron-lined cylinder assemblies flow coolant in the most efficient way possible. From the water pump, coolant goes through the upper half of the horizontally split crankcase and directly to the bottoms of the cylinders below the exhaust port, the hottest point of the engine.

That's right. The crankcases are in part liquid-cooled, but more important, the coolant, having been drawn out of the radiator by the pump, goes pretty directly to the area in greatest need of cooling. That makes more sense than running the coolest water into the cylinder heads preheating it before it reaches the exhaust area. Coolant then passes up through the cylinder, through the head and to the top of the single-core radiator. No auxiliary cooling fan clutters the RG; it is, after all, built to be in motion.

The six-speed transmission operates through a seven-plate wet clutch driven via a helical gear off the right side of the crank. The upper five ratios, grouped fairly close together, help the rider to cope with the narrow 2000-rpm powerband. In practice, first gear is a starting gear; it takes some over revving to keep the engine pulling strong on the first/second break. A quick note here to you road ruffians make sure your Gamma is far ahead of the pack if your personal road has a first-gear hairpin. Otherwise, some pursuing rider latched to you like a bad odor will snake past on the exit when it's time to shift.

You kick to start the Gamma. That's okay; when was the last time a serious racer pushed a button on the line? Our Gamma had the usual warning lights with a cute extra, the You Are Exceeding The National Speed Limit In Japan light. Our RG was a domestic (Japan only) model, and it conformed to Japanese Vehicle Code regulations. Motor vehicles in Japan must have little lights that flare up and stay lit any time offenders exceed 80 kph (50 mph) with their vehicles. By our reckoning, we had the Too Fast (Too Fun) light operating on the same schedule as, oh well, the spark plugs.

This is the motorcycle for the few, the proud, the crazy. Which means that Suzuki could sell a handful of these bikes in the United States—if they were EPA legal, and they're not. Yes, we know about catalytic converters for these things, and yes, it would be wonderful as, say, a 400. We love it as a 250, heaven knows, but still, folks, even as a 400 the Gamma would be an expensive toy, misunderstood and unwanted in Peoria. The narrow handlebars and high-mounted footpegs conspire with the firm seat to have you planning for your second stop almost before you finish your first one. Size for size, the Gamma makes a Phantom jet seem parsimonious. The RG swills at 35 mpg, so your sore butt will be out of the saddle in 120 miles. You'll either be pumping gas or walking. We recommend a hip flask for extra CCI oil because the RG empties its two-stroke oil tank every other gas stop.

Forget touring considerations. The 250 Gamma is too direct, too connected with the pavement for that. Like a race bike, it gives its rider access to every capability in the motorcycle book of operations. The bike/rider communication is instantaneous, without the filtering and deadening qualities produced by excessive weight, slow steering, spongy suspension and soft braking. The Gamma turns, stops, responds; no delays, no questions. And you better be good without question, too. The RG-Gamma prefers smooth, sure guidance from its rider. If you get sloppy and don't know where you're going, not only will your cornering lines become haphazard, you'll have a hell of a time keeping the engine operating in its 2000-rpm window.

Sure, the Gamma will work as a Saturday-cruise-to-the-beach special, and be wasted doing so. In the month we've spent with the RG, it's happier threatening life, limb and license. No, it's not unsafe; quite to the contrary, it'll get you out of trouble as fast as you get yourself into it. Some motorcycles are fun to ride fast, others—better yet—are willing accomplices to misbehavior, and still others—best of all— are almost bonafide perpetrators themselves.

Suzuki has done the responsible thing, Law and Order wise, mind you. They've kept the Gamma and its little EPA problem out of the United States. Yeah, and succeeded in making the few and the proud even crazier.

Source Cycle 1984

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |