|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

Suzuki RGV 250

|

| . |

|

Model. |

Suzuki RGV 250 |

|

Year |

1990 |

|

Engine |

Two stroke, 90° V- twin, reed valve |

|

Capacity |

249 cc / 15.2 cu in |

| Bore x Stroke | 56 x 50.6 mm |

| Compression Ratio | 7.5 :1 |

| Cooling System | Liquid cooled |

|

Induction |

2 x Mikuni VM32SS semi-flat carburetors |

|

Ignition |

Pointless Electrical Ignition |

|

Spark Plug |

NGK BR9ES |

|

Battery |

12V, 5Ah |

|

Starting |

Kick |

|

Max Power |

35.7 kW / 49 hp @ 9500 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

40 Nm / 4.1 kgf-m / 29.5 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm |

|

Clutch |

Wet, multi-plate |

|

Transmission |

6 Speed, constant mesh |

|

Primary Reduction |

2.565 (59/23) |

|

Gear Ratios |

1st 2.454 (27/11) / 2nd 1.625 (26/16) / 3rd 1.235 (21/17) / 4th 1.045 (23/22) / 5th 0.916 (22/24) / 6th 0.840 (21/25) |

|

Final Drive |

Chain, DID520V2, 114 links |

|

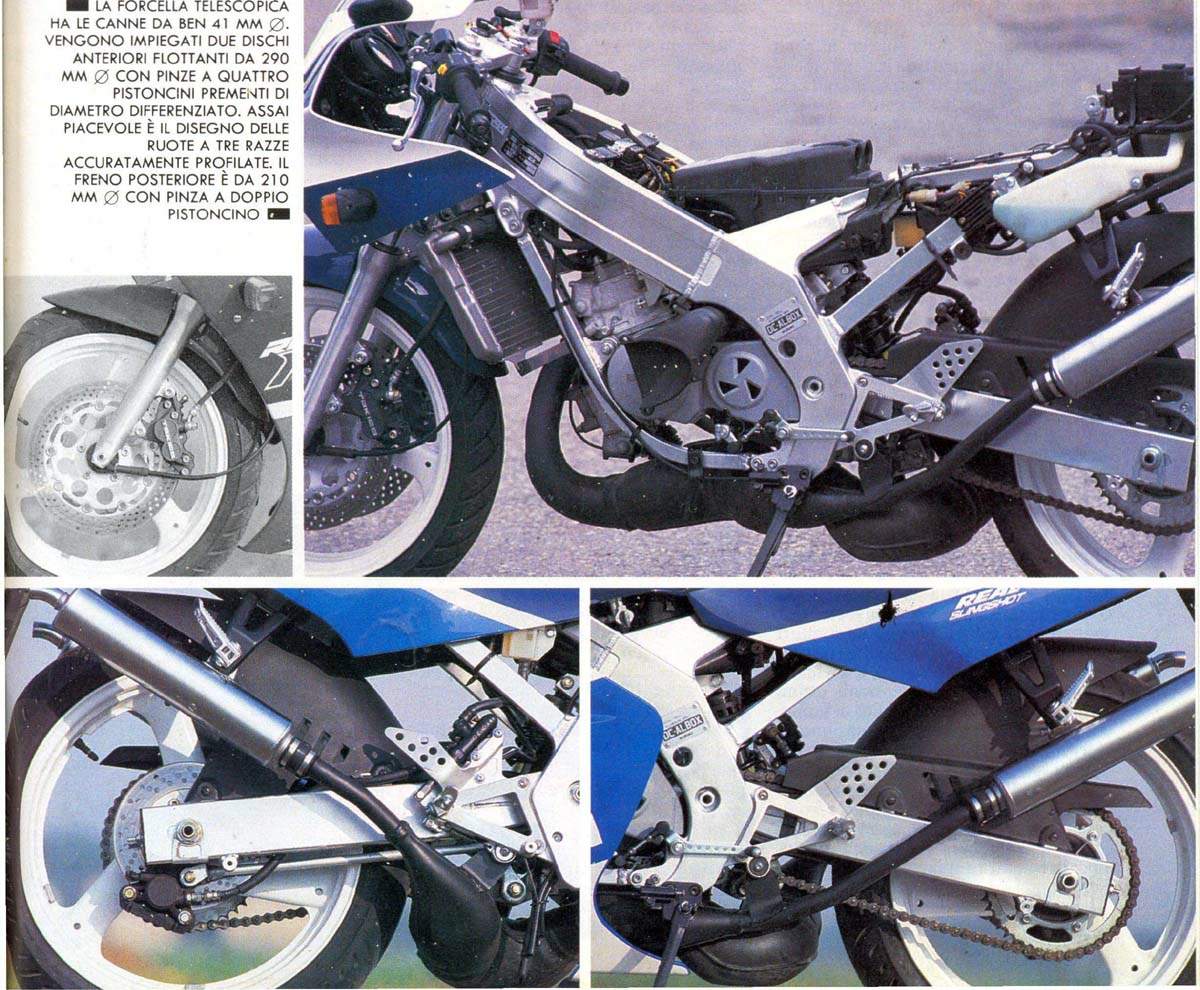

Front Suspension |

Telescopic fork, 5-way adjustable with anti-dive, oil dampened |

|

Front Wheel Travel |

120 mm / 4.7 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Full Floater, mono-shock, gas/oil damped, 7-way adjustable |

|

Rear Wheel Travel |

140 mm / 5.5 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2 x 290 mm Discs ,4 piston calipers |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 210 mm disc, 1 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

110/70-17 |

|

Rear Tyre |

140/60-18 |

|

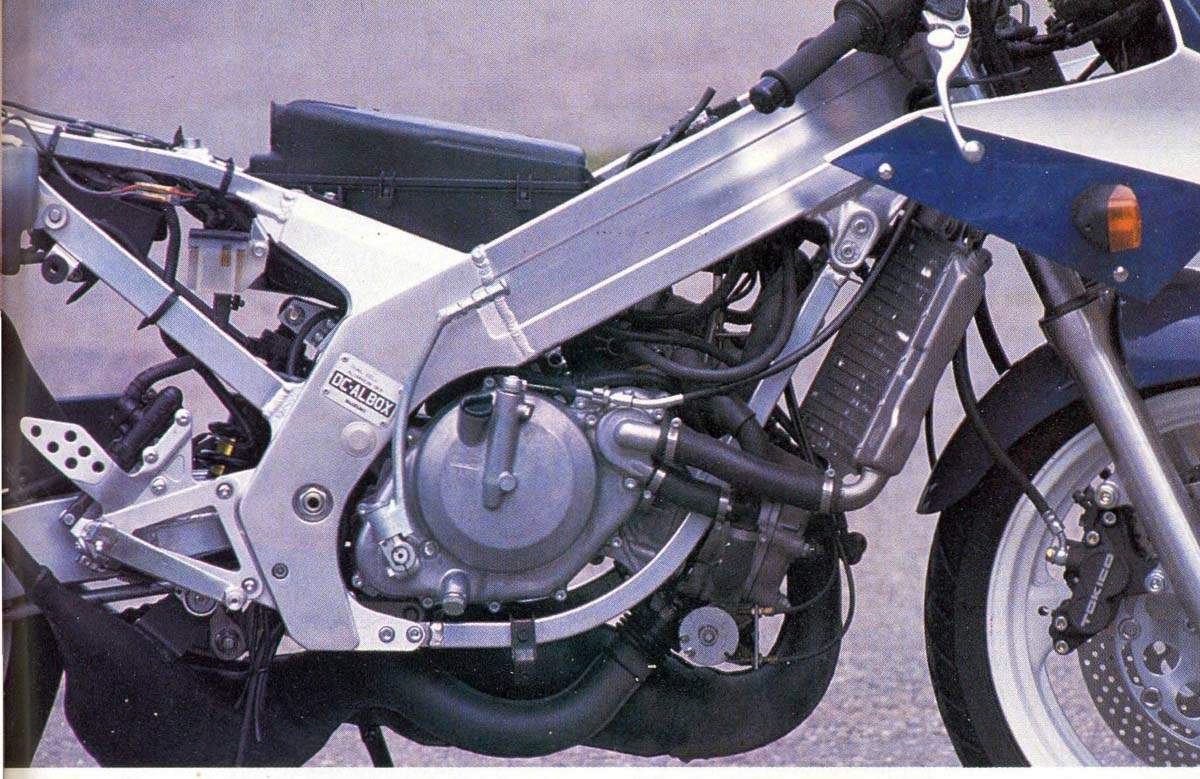

Frame |

Twin spar, aluminium |

|

Rake |

26o |

|

Trail |

110 mm / 4.3 in |

|

Dimensions |

Length: 2015 mm / 79.3 in Width: 695 mm / 27.4 in Height: 1065 mm / 41.9 in |

|

Wheelbase |

1375 mm / 54.1 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

120 mm / 4.7 in |

|

Seat Height |

755 mm / 29.7 in |

|

Turning Radius |

3.1 m / 10.2 ft |

|

Lean Angle |

58° |

|

Dry Weight |

128 kg / 282 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

17 Litres / 4.5 US gal / 3.7 Imp gal |

|

Oil Capacity |

1.1 Litres / 12 US qt / 1.0 Imp qt |

|

Consumption Average |

7.8 L/100 km / 12.8 km/l / 30 US mpg / 36.0 Imp mpg |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

12.9 sec / 160 km/ / 100 mph |

|

Top Speed |

202 km/h / 125 mph |

|

Road Test |

Motosprint 1989 |

Review

Led astray by the lure of wild powerbands and wilder tank-slappers we present: KR-1S, RGV250M, TZR250 and, just for old time's sake, RD350LC-F. We trundled them across the fens, hurled them up the Cat and Fiddle road (the A53 between Buxton and Mace), sat them in a traffic jam in Manchester and finally whupped them round the ultra-tight Three Sisters race track near Wigan. We even brought most of them back again.

YAMAHA TZR250

They wouldn't let it lie

Well, actually, they would've let it lie, but we wouldn't listen. The TZR is now out of production, and Yamaha aren't keen to push the remaining stocks. They would rather let them slip quietly away without any fuss that might detract from the almost certain 1992 launch of the all-new TZR.

It's a shame really, because there is life in the TZR yet as road bike. It may no longer be able to cut it on the track, but the combination of stable handling and reliable power means it can still keep up on all but the fastest roads.

For any model to survive so long virtually unchanged is testament to the soundness of the original design. Rupert: 'It's the perfect mix of race technology and practical useability.'

On the Cat and Fiddle and surrounding roads the TZR was probably the easiest to get the best from. Chassis, brakes and power harmonise so well that the rider can concentrate entirely on the road ahead, confident that the bike won't spring any nasty surprises. Stephen: 'I really don't think you can fault it - you can slam it into corners with the brakes full on and it'll still go round, with the only protest coming from the tyres.'

Where the RGV would sit up violently under mid corner braking, and the KR-1S felt as though the front wheel would tuck under, the TZR stayed gently on line until the rider decided what to do next. This is the sort of behaviour that can save your bacon on unfamiliar roads, especially when they are flanked by frightening drops.

On paper at least, the TZR is the slowest steering of the 250s, sharing its rake and trail figures with the 350 powervalve, and it may be this which helps give straight line stability that's no more than a dream for KR-1S owners. Cresting small rises on the Cat and Fiddle, or launching off yet another cratered bump on my ride across the fens to work, the TZR would lift its front wheel slightly, give just a little wibble, then smack rather satisfyingly back down to earth before continuing on its way as though nothing had happened.

On the same fen roads, the KR-1S would go from lock to lock before settling down, and meeting another bump before the steering had sorted itself out was a deeply distressing experience.

At Three Sistefs the TZR's tyres quickly became the limiting factor. Yamaha aren't doing themselves, or the bike, any favours by letting it out of the factory with tyres so far behind the rest of the bike. Trevor: 'The standard tyres are disgusting.' This was something we all agreed on, although Rupert was more polite: 'The tyres grip OK but offer nothing like the feel and grip of the RGV/KR-1S. Aftermarket stickies would improve things but it'll never quite be up to the latest standard. It'd be enough for most people though.' By all accounts a change to Avon AM22/23 rubber does the job nicely.

Lousy tyres aside, the TZR feels totally at home at the track, though it rapidly runs out of ground clearance - if you don't hang off as far as possible it feels as though the footrest is about to dig in and lift the whole bike off the floor. The braking lacks some of the awesome ability of the newer 250s - 'Plenty of power, plenty of feel. But the KR-1S and RGV have even more.' - Rupert. It is easier to use all that's available, though, and a panic application doesn't necessarily spell disaster. Trevor: 'The single disc works fine, but requires further clenching of the fingers after the initial grab.'

Stepping onto the TZR directly after the RGV, it's easy to see the Yamaha as crude and unsophisticated, but the fact is that the basic package is so good it doesn't need frills. Stephen, commenting on the suspension options, pointed out: 'There's not much adjustment because it's not needed.' The best thing to do with a TZR is to set the rear preload to suit your own bulk, then get on with riding it.

Ten minutes in town and the TZR shows the other side of its character. Apart from some mild clucking between 5 and 6,000 revs, when the powervalve can't decide whether to open or close, the motor is utterly docile in traffic. It puts up with extended low-speed running without complaint, all the controls and switchgear are sensibly designed and easy to use, and the well-shaped seat and relatively upright position make it easy to trickle through jams where the Kawasaki and Suzuki produce a wrist-heavy weave.

Trevor summed up the joys of long-term TZR ownership: 'More friendly than the others. Starts first time, the mirrors are useable and the seat is comfortable up to the first tank refill' If that doesn't sound very far, bear in mind that the other 250s were probably designed by an unemployed set designer from a Japanese TV game show specialising in personal humiliation. Stephen added: 'The TZR is easy to clean, good pillion seat, luggage can be carried, lasts for ages. Bought by sensible people.' Except for you, Stephen.

If all this seems to be singing the TZR's praises rather too loudly, then I apologise, but Trevor was its loudest critic, and the worst comments he could make were to suggest that it was under-geared (hitting peak revs long before the timing lights at Bruntingthorpe), and to point out a grabby clutch. The TZR is dead. I wonder if the new one will live as long.

YAMAHA RD350LC-F They shouldn 't let it lie But they're going to just the same. Like the TZR, the good old powervalve is

being pensioned off. Muted by noise restrictions, choked by emission controls

and rendered obsolete by ever newer and faster models, the 350 has come to the

end of its eight year run. Rather the oddball in our test, the 350 was invited along to give us

something to ride when the others got too uncomfortable, and to allow Rupert to

exercise his well known concern for endangered species of all kinds. Rupert loves this bike: 'I love this bike,' he said. See? The

350 arrived with a half worn OE front tyre, and a similarly dogeared Metzeler

ME99 rear. Rupert: 'Felt awful and yawed into comers. Front/rear mismatch bad

news. Dodgy in the wet' The first port of call, therefore, was to kneel at

the shrine of Steve Lythgoe at Sharples (0204 54698). Steve, fount of all

knowledge on things black and sticky, recommended Pirelli Demons but didn't have

a front one in stock. A few phone calls and the Manchester Pirelli distributors

had some on the doorstep within a couple of hours. Thank you Ivan. As promised, the Demons transformed the feel of the bike: 'The

Pirellis wade the RD feel planted. Smooth banking, chuckable and more stable.

Footrest down no prob. The mutt's nuts for the RD.' - Rupert.

(Trevor was even moved to ask if they were available for his pushbike.) The 350 feels understandably dated: "70s superbike construction — lots of

space inside fairing and frame means reduced rigidity.' - Rupert. But in

spite of this, it manages to be more than the sum of its parts. The forks flex,

the rear shock overheats and the brakes need the grip of a gorilla to overcome

spongy hoses and haul to a stop. None of this is really a criticism; the bike is

so balanced that no one thing holds it back. On the road or the track, the

suspension and frame give plenty of feedback. Rupert again: 'The chassis

feels great - really confidence inspiring.' Rupert went on to attribute much of the 350's manageability to the

old-fashioned seating position, which makes it easy to shift weight around

between hands, feet and backside. This led Trevor to describe it as: 'The

tourer of the two-strokes. More of the old sit-up-and-beg stance. Rolls Royce

seat compared to the rest.' I was particularly grateful for the comfy seat on the run back from Three

Sisters a few hours after my unscheduled track inspection. There was no way I

could sit on any of the 250s - even the TZR - but the 350 was comfortable enough

to allow me to keep up with the others without aggravating my bashed left arm

and shoulder.

For me, the best thing about the 350 is the way it lets the rider know when

it's time to back off. The Kawasaki and Suzuki walk a very fine line between

fine handling and unmanageability - you either get it right or very, very wrong.

The 350 reaches a sort of plateau area just before it reaches its real limits.

It's possible to go a fair bit faster if you up your concentration levels; it's

equally possible to bumble along and let the bike do the work, confident that

it'll forgive you for the odd unconventional line or unexpected emergency stop. The motor in our bike had been seized and completely rebuilt just before we

borrowed it, and was running rather woolly. Rupert tells it like it is: '

Warms slow, spews on choke. Lots of clatter on overrun at mid revs made worse by

worn shock absorbers in clutch basket. Bit more of a noticeable power step than

others. Never feels crisp and agonisingly beautiful like the KR-1S. Pulls good

wheelies off the throttle. Power valve opens/shuts at 5,500rpm — engine hunts

and clucks like a Norton Fl. Transmission backlash makes this worse. Dies at

9,400rpm. Ledar pipes increase rev range. Will go faster with higher gearing,

but lower is better — the motor is in the real road speed range then.'

Thank you. Now, where were we? Ah, yes. It was no surprise that the RD was the easiest to get on with in

town. Even running rich it was still possible to stay at low revs. The milder

tuning and extra 100cc makes for better roll-ons than the 250s, too. The RD is a relatively cheap, freely available way to get to work all week,

get your knee down at the weekend and take on holiday in the summer. Direct

comparisons are meaningless. This is one of those rare bikes that is, quite

literally, in a class of its own. SUZUKI RGV250M They couldn't let it lie It was a matter of honour, I suppose, that Suzuki should try to follow up

their return to Grand Prix with a similarly impressive return to the streets and

roundabouts where those races are re-run every Saturday night. Unfortunately for

them the old RGV didn't really make an impression on the track (in the UK - it

did in France - RP), and when it came to laying down the deposit for a

road-going 250, the RGV's styling wasn't seductive enough to get over being a

few horsepower down on the KR-1S. The power shortfall is still there, so perhaps with the M, Suzuki are trying

to win sales through sheer novelty value - the first 250 with upside-down forks,

banana swing arm and both exhausts exiting on the same side. They certainly aren't trying to win anyone over by making them comfortable.

Trevor: 'It may be first in the pose department, but it's definitely last in

practicality. Bum up, head down sitting position hurts wrists, bum, back, neck.

You need to be an unbalanced ex horse-jockey.' Rupert rode the RGV from

Wigan to Peterborough, and complained that his bottom started hurting at

Donington. He had other complaints to make about the position, too: 'The bars

are too low. Even at the track I'd have preferred them higher so I could wrestle

the bugger, turn it more easily. They're only that low to keep you out of the

wind, and the price you pay when you ride slowly is high.' If you can't wrestle with the bars, you've always got body weight. The RGV

responds to pressure on the footrests more precisely than most bikes do to

commands from the bars. ' Weight pushed onto the foot-rests will give the

required angle of lean. The bars are there to give stability.' - Trevor. On bumpy fen roads, the RGV produced the most frightening tank-slappers I

have ever had the misfortune to experience. The bars weren't wrenched from lock

to lock as violently as on the Kawasaki, but they took longer to settle down -

time that you don't always have when you're headed for the dyke and the coypu

are hungry. It's strange, but the RGV only behaved like this in a straight line. On my way home from work there is a long, left-hand bend. On its apex is the

scar of a long-forgotten roadwork, running from one side of the road to the

other and sitting proud of the surface. Hitting this cranked over the Kawasaki

kicked its front wheel towards right lock, and threatened worse, before coming

back on course. On the same bend, at similar speed, the RGV hit the bump,

bounced, but continued on line. Elsewhere on the road, the RGV would sit up under braking, a tendency that

went from mild to awful depending on suspension settings. As a rule, the nearer

we got to curing it, the worse the suspension behaved the rest of the time. In

the end, it's something you have to learn to live with. Stephen suggested that,

if you really need to scrub off speed in a corner, then you should use your

knee. Anyone buying an RGV as daily transport needs his or her head examined. Apart

from the obvious disadvantage of acute discomfort and atrocious fuel

consumption, pick-up from rest causes problems. Trevor: 'Poor clutch action

when cold. Sometimes stalls when engaging first. Clutch riding required up to

three grand to avoid laughs from car drivers going from traffic lights.' Once the bike's moving, other irritating traits make themselves known. The

Suzuki's gearbox is not up to the standard of the rest of the bike - the first

three gears clunk like a car door, though after that it's as slick as you could

wish. When the oil light glows you discover the oil filler can only be reached

with a funnel (and how many paddock jackets have room for a funnel these days?).

Our bike usually ended up with overspill dripping onto the rear tyre. The

pillion seat is a sick joke. The kickstart lever vibrates outwards whilst on the

move, then catches your leg when you try to put a foot down to stop. The motor is in a very high state of tune straight from the factory - peak

power and torque are in the same place, and Stephen felt this was bad news for

long term ownership: 'It'll wear out very quick — the engine's got the nuts

tuned off it.' This translates into a very peaky feel - the motor won't

always pull 70mph in top, but brilliant carburation helps to make it useable out

of the powerband, so long as you don't expect any real acceleration. It's as if,

when it's not at peak power, the motor is just marking time. The only problem

was on the overrun: 'Excellent carburation from tickover to 12,000rpm, except

rolling off slightly at high revs, eg: passing a car and pulling in. The motor

stutters and clacks quite violently - you have to shut off or accelerate. It

would be nice if it was crisp and clean at this point.' - Rupert. Public roads can never give a true indication of the RGV's capabilities. This

is a bike designed to be ridden on smooth, twisty tarmac with nothing coming the

other way. Once you know which way the track turns the RGV will take get you

round quicker than you thought possible. It is capable of taking you to

astounding lean angles and it can stop as fast as you dare. It is not, however, an easy bike to ride fast. It will respond to precise and

knowledgeable control by taking you to a smooth, fast lap. It will respond to

nervous input by spitting you off. The RGV is at a stage of development where

there is no room for anything other than perfection. You sometimes feel as

though you've reached the RGV's limits, but the limits are your own. Rupert: 'At 80-110mph it just glides along like a low flying aircraft.

Superb poise - change the angle of lean and it'll immediately assume the new

set, a bit like when a hairdresser moves your head to a different position. The

front feels mega pushable. Astounding grip at crazy angles - I've never seen

anyone lean over so far on road tyres as Stephen at Three Sisters.' Those

marvellous tyres, though, pay for their superb grip by wearing out and

spitting off bits of rubber onto the bellypan as rapidly as anything with NOT

FOR HIGHWAY USE on the sidewall. The final say on the RGV has to go to Stephen: 'Even though it's down on

power, I think I could win a club race on one of these.' KAWASAKI KR-1S I had to let it lie One second I was following Stephen out of the hairpin and into the downhill

left hander, the next I was sliding along on my back. The front had gone so

quickly it wasn't until I'd ground to a halt that I realised what had happened. Unfortunately this was before the RGV arrived at Three Sisters, so we

couldn't get a direct track comparison, but even the few laps we managed had

shown up what Stephen considers an inherent problem with the Kawasaki's front

suspension: 'Very quick steering - too quick. The head angle is too steep and

the forks too hard for road use. The front seems unsure of where it wants to go

at high speed. Slaps violently. If you hit a bump changing line or braking

you're in deep shit - you just have to try to hold on 'til it calms down.' The forks seem to have too little compression damping and too much rebound -

under braking they dive straight to full compression and then stay there,

chattering over bumps so that it's impossible to use all the incredible power of

the front brake. 'Like trying to dig up concrete with a garden fork,'

was how Trevor put it. Stephen plans to try longer, softer springs and slightly more oil, but of a

lighter grade, on his own KR-1S. The rear suspension is fine for going fast, though the shock tends to top out

on the standard rebound settings - going up to position two cures that, any more

and it begins to chatter. The other factor preventing full use of the brakes is the seating position,

which is the worst of the 250s. 'Jump on a desk and kneel on it, then put

your clenched fists flat on the desk face down. Then look up. That's a KR-1S

riding position.' - Rupert. Like the RGV, the low bars are too far away for the rider to steer as

effectively as possible, or to brace himself against the brakes. The Kawasaki

has one of the most powerful brakes currently available on a motorcycle, but you

can stop quicker on the RGV because it's easier to control. These criticisms are

only in relation to the RGV's excellence. Ridden on its own the KR-1S seems like

the most responsive bike in the world. The intensely quick steering feels as though it will tuck the front under and

doesn't feel as controllable as the RGV. The grip from the KR-1S's radials can

get you out of a lot of trouble, though. Trevor: 'If superglue was radial,

this would be the black, circular version.' Rupert was similarly knocked out

by the combination of grip and handling: 'Bloody unbelievable and a rare

experience even for someone who roadtests bikes all year. Controlled-squirt

power enables you to use all the grip. Ride this bike if you want to know what

racer handling is. Excellent motorcycle.' In the real world genuine excellence matters less to most people than

perceived performance. Marginally out-handled and comprehensively out-posed by

the RGV, the KR-1S will have to make the most of its power advantage if it is to

maintain sales. On the dyno, the perfectly set up RGV gave a max of 53.7hp. The

Kawasaki pushed out 55.5, but Ledar's Colin Taylor reckoned it was over-oiling

and running rich, and that there were several more horses to be gained by

careful setting up. Even as it was, Rupert raved about the motor: 'Crisp and progressive

buildup of power. Mighty impressive. Minimal hunting on a neutral or closed

throttle. At 8,000rpm it just goes Waaaa! (To simulate this sound, take a

large sheet of calico - available from all good drapers - and tear it quickly

from top to bottom - KR) (Must be warp to weft — JR) Addictive.' Get caught in the flat spot just before it takes off, though, and it's easy

to get bogged down. Trevor: 'If you're not at 7,000rpm then roll-ons become

hill-climbs.' Once in the power the KR-1S pulls up to 136mph, stomping on the RGV by nearly

10mph. This has more to do with gearing than with the small power difference,

but higher gearing would lose the RGV the small advantage it has away from the

line. Urban riding is not the Kawasaki's strong point, but it is no worse than the

RGV. Manhole covers and potholes throw you against the tank, even at low speed.

This puts even more weight on your already overloaded wrists, and the quick

steering which is such a joy at the track wanders around like steering through

treacle. The bike doesn't start working until it reaches the sort of speeds

which leave your licence extremely vulnerable. Trevor found the motor absolutely useless below 3,000rpm, but tractable

enough between there and 7,500, after which: ' Warp drive that James T Kirk

would kill for. And the gears are as precise as climbing stairs.' The only

problem with the gearbox is an occasional need to hunt around for neutral -

annoying at lights, but as most people sit in gear and rev the engine they won't

notice. On the forecourt, filling up with two stroke is easier than on the RGV, but

entails taking off the pillion seat, getting to the toolkit, then unbolting the

main seat to access the tank. The best smelling oil for the KR-1S is Silkolene

Pro-2, by the way. If I wanted to get really picky I could say that the indicator switch is too

fiddly for a gloved thumb, the mirrors reflect your elbows, the lights are too

diffused to offer serious illumination and it hurts when you fall off. But these

things are of no relevance to anyone who wants one of these bikes. Like the RGV,

the KR's a racer with lights. It'll be bought on the back of track success and

fashion credentials and bugger everything else.

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |