|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

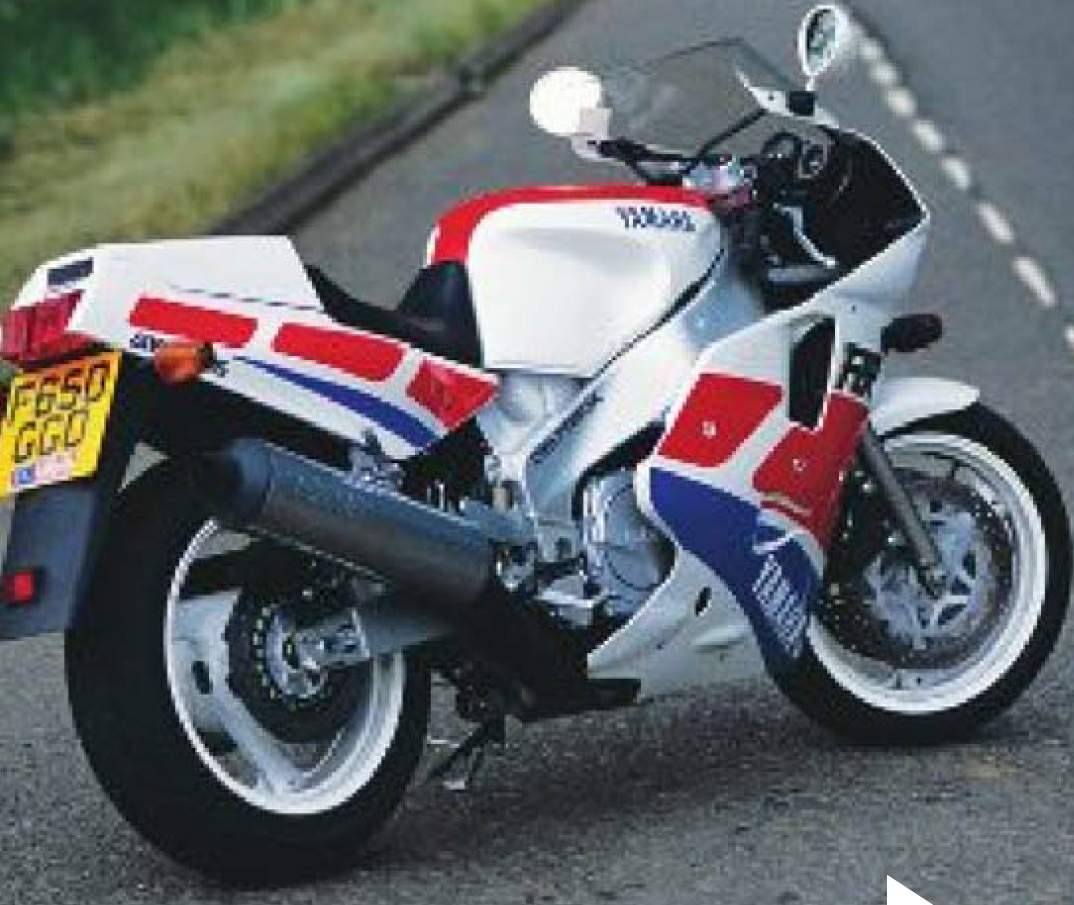

Yamaha FZR 1000 EXUP |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Yamaha FZR 1000 EXUP |

|

Year |

1989 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, 35° forward inclined transverse four cylinder, DOHC, 5 valves per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

1002 cc / 61.2 cu/in |

|

Bore x Stroke |

75.5 x 56 mm |

|

Cooling System |

Liquid cooled |

|

Compression Ratio |

12.0:1 |

| Compression Pressure | 14kg/cm2 (1400kPa, 199 psi) |

| Compression Range |

13.6kg/cm2

(1360kPa, 194psi) minimum |

|

Lubrication |

Wet sump |

| Exhaust | EXUP exhaust control system |

|

Induction |

4x 38mm Mikuni BDST carburetors |

|

Ignition |

TCI digital ignition |

| Battery | YB14L 12V 14AH |

|

Starting |

Electric |

|

Max Power |

145 hp / 105.7 kW @ 10000 rpm |

| Max Power Rear Tyre | 131.7 hp @ 10500 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

10.9 kgf-m / 107 Nm @ 8500 rpm |

|

Clutch |

Wet, multi-disc |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

|

Final Drive |

Chain 532ZLV, 110 Links |

| Secondary Reduction Ratio | 68/41 (1.659) |

|

Frame |

Diamond Deltabox |

|

Front Suspension |

43mm Telehydraulic for adjustable preload |

|

Front Wheel Travel |

120 mm / 4.7 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Gas/oil single shock, rising rate adjustable preload and damping |

|

Rear Wheel Travel |

130 mm / 5.1 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 320mm discs 4 piston calipers |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 267mm disc 1 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

130/60 VR17 |

|

Rear Tyre |

170/60 VR17 |

|

Rake |

26.7° |

|

Trail |

110mm / 4.33 in |

|

Dimensions |

Length 2200 mm / 86.8 in Width 730 mm / 28.7 in Height 1160 mm / 45.7 in |

|

Wheelbase |

1460 mm / 57.5 in |

|

Seat Height |

765 mm / 30.1 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

135 mm / 5.3 in |

|

Dry Weight |

209l kg / 460 lbs |

|

Wet Weight |

236 kg / 520 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

19 Litres / 4.2 gal |

| Consumption Average | 16.3 km/lit |

| Braking 60 - 0 / 100 - 0 | 13.1 m / 37.0m |

| Standing ¼ Mile | 10.1 sec / 216.8 km/h |

| Top Speed | 273.4 km/h / 169.8 mph |

| Road Test |

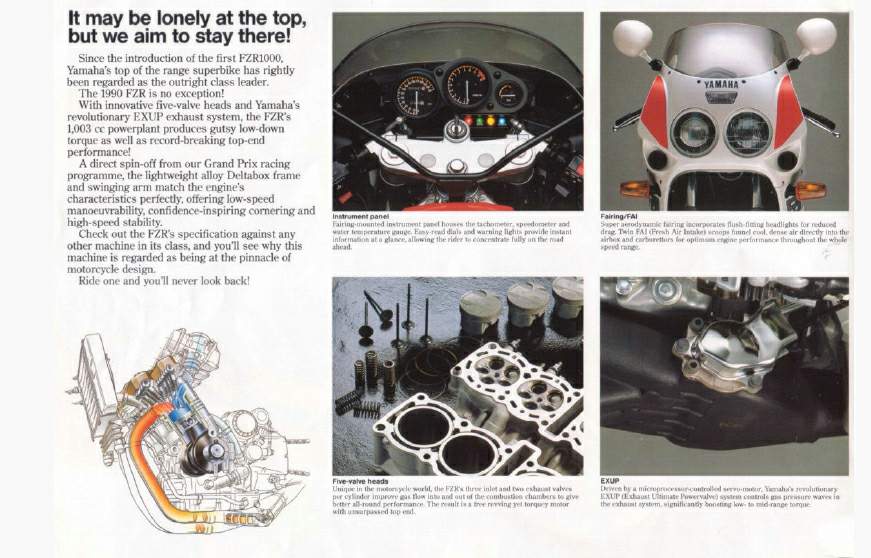

Second generation

In 1989 the second generation, called the FZR 1000 EXUP, marked a further step up the ladder to high perfection supersport. In spite of the motorcycle world expecting a revised version of the earlier machine, the "EXUP", as it was nicknamed by enthusiasts later, was a totally new machine. The world's motorcycle press testers were again enthusiastic, when they were given the opportunity on October 25-28, 1988 to test the bike at Laguna Seca racetrack in Monterrey, California. The engine now had an increased displacement of 1002 cc and higher performance with 145 HP. In spite of higher displacement its size was 8 mm shorter and more compact, due to a revised inclination angle of the cylinders to 35°. Valve angles and sizes had been changed, as well as the camshaft timing. Bigger carburettors helped boost performance and the crankshaft had been strengthened, along with countless other modifications.

THE 1989 YAMAHA FZR1000 - SECOND GENERATION GENESIS

The dictionary defines genesis as "development into being by

growth or evolution" - which perfectly describes Yamaha's Concept that led to

the award-winning FZ and FZR models and the race-winning YZF which swept to

victory in the last two successive Suzuka Eight Hours Races.

The "Genesis" concept as stated by Yamaha was the parallel development of engine

and chassis design. each playing its part in making the other more effective. lt

was evolved by engineers who realised that building a good engine and a good

chassis did not necessarily mean a good motorcycle unless the two were in

technical harmony with one another.

That "development by growth or evolution" continues with the

1989 Yamaha FZR 1000 updated and uprated by lessons learned on the racetrack

with the YZF.

Featuring a new Deltabox frame, shorter and more compact dimensions, the

remarkable EXUP exhaust power control system and improved engine design and

performance, the latest evolution of the FZR1000 is the most balanced performer

in the sportbike world.

The original FZR 1000 won "Machine of the Year" awards from magazine readers around the world as soon as it was announced. Yamaha are confident that this "second generation Genesis" will be equally well received. After all, it's the only sensible choice for those who demand the very best.

ENGINE

With its brilliant 5-valve cylinder head, slant block and

efficient intake and exhaust systems. the FZR 1000 engine has an established

place in motorcycling history. For 1989 it has been improved even further.

A brief summary of the new engine's features are: a higher redline thanks to a

lighter valve train, more displacement (1002 cc). a higher compression ratio and

redesigned combustion chamber with straighter intake ports. bigger carburettors,

a reduction in frictional losses with thinner rings, and the addition of the

remarkable EXUP exhaust control system. Now let's take a look at the details.

The new engine has been shortened by 8mm. This was accomplished by shortening the length of the valves and lifters and using a new camshaft case. The shorter valve stem length also allowed for a slight increase in valve angle. The middle intake valve angle has increased from 9 degrees to 10.5 degrees, the outer intakes from 17 to 18.5 degrees, and the exhausts from 13 to 13.5 degrees. These more idealized angles and the complementary improvements to port shapes increase engine efficiency for higher power output. Other changes to the valve train include exhaust lifters increased in diameter from 20mm to 22.5mm for improved reliability, and an overall reduction in valve weight, thanks to shorter sterns and a reduction in stern diameter from 5mm to 4.5mm. This lighter valve train, combined with stiffer valve springs, permits a 500 mm higher redline and, consequently, more top-end power. Valve head diameter remains unchanged.

An increase in bore from 75rnm to 75.Smm brings displacement up from 989cc to 1002cc. Combined with reshaped combustion chamber and ports and slightly less dished pistons, this raises the compression ratio from 11.2: 1 to 12:1. The result is increased power and torque throughout the mm range and improved engine efficiency.

The shape of the intake tracts has also been changed. Short and straight, they allow for smoother air flow and increased intake performance. A change in carburettors from Mikuni BDS37 to BDST38 improves breathing even further. In addition to offering more venturi area and a rounder venturi cross section, the venturi itself is much straighter and shaped like an air funnel. These changes greatly reduce flow resistance for improved efficiency and more power. Throttle response is also better. And to make sure these bigger carbs get plenty of fuel regardless of engine bad, fuel pump capacity has also been increased.

Moving further down, we find new pistons and rings. While the top ring remains unchanged, the second ring has been thinned from 1mm to 0.8mm, and the oil ring from 2mm to 1.5mm. The result, when multiplied by four, is a significant reduction in frictional losses and consequent gain in engine output.

The connecting rods have also been changed to reduce friction and the resulting power loss. By increasing the diameter of the piston pin from 18mm to 19mm, rotating frictional loss has been reduced. This reduction in friction also means increased reliability at the piston pin. In this way, many small improvements can add up to big gains in power and reliability. Power was also found by increasing the air cleaner volume from 7.1 liter to 8.1 liter for improved engine breathing.

To better control temperatures in this more powerful engine,

radiator capacity is increased from

17,000 cal to 21,000 cab. This prevents overheating during sustained periods of

high-rpm, high-load operation.

Even the transmission benefits from detail improvements. By

using counter-tapered (back-cut) engagement dogs on the gears, gear engagement

is much more positive and transmission reliability is increased to cope with the

increase in power.

In summation, virtually every area of the FZR 1000 engine has been improved.

More powerful and more reliable, it is also more compact and more refined. lt's

the second generation

EXUP (Exhaust Ultimate Powervalve)

One of the most significant features on the new FZR1000 is the EXUP exhaust control system. Another Yamaha invention; in principle it is much like the YPVS system which improves 2-stroke engine performance by changing exhaust tuning in response to changes in engine mm.

As more horsepower is designed into production engines, the smooth powerband so desirable for the street is replaced by the "peaky", lumpy power curve of the racing engine. Especially pronounced with high-performance, 4-into- 1 exhausts, this results in a fiat spot at about two-thirds of peak-torque mm and a rough idle.

Technically speaking, when the exhaust valve opens, residual combustion pressure in the cylinder rushes in to the exhaust pipe, creating a primary "positive" pressure wave moving towards to collector (muffler). Upon reaching the collector, it expands, sending a primary "negative" wave back toward the cylinder. The header continues to reverberate, alternating positive and negative. primary, secondary and tertiary.

Header pipe length is set so that the primary "negative" wave reaches the cylinder at valve overlap (the brief instant when both intake and exhaust valves are slightly open). This negative or "suction" wave does two things. lt pulls residual exhaust gas out of the cylinder, and it starts the flow of fresh fuel/air mixture through the intake valve.

Unfortunately, because these positive and negative pressure waves move through the header pipes at uniform speed regardless of engine rpm, at lower rpm the primary "negative" wave arrives too soon (before overlap), and in its place a primary "positive" wave arrives at valve overlap. This positive wave forces exhaust gasses back into the cylinder, diluting the charge, and it blows back through the carburettor, delaying intake and causing double carburetion (carburetion in the wrong direction). This is what causes the dreaded race-engine flat spot.

Prior to EXUP, the only way to smooth out power delivery was to sacrifice performance (less overlap, use of less resonant exhaust pipes, etc.).

Think of EXUP as an exhaust throttle. By placing a rotary valve driven by a microcomputer-controlled servomotor between the header pipes and the collector, Yamaha engineers were able to control the pressure waves. The Computer senses engine speed from the ignition. By choosing this valve progressively as rpm decreases, the harmful positive pressure wave is prevented from reaching the cylinder at valve overlap. Double carburetion is eliminated, torque rises back to a normal level and driveability is restored.

EXUP also reduces exhaust emissions at idle by producing back pressure that reduces boss of fresh charge through the exhaust. The idle is also smoother and steadier. And a new muffler has enlarged capacity to efficiently quiet the increased power.

Equipped with EXUP, the engine produces about 10% more top-end power than an engine without EXUP. Most importantly, driveability and throttle control are greatly improved in that critical upper portion of the power band. There is an astonishing 30 to 40% increase in bow- and mid-range torque and smoother acceleration. The idle is much smoother: 30 to 50% less fluctuation at idle mm. The exhaust note at idle is quieter. And, hydrocarbon emissions are reduced.

In short, riders enjoy the best of both worlds - high-performance power with street engine tractability. Another first from Yamaha.

NEW DELTABOX FRAME

The aluminium Deltabox frame is the most technically refined frame on the market. Light, rigid, and extremely resistant to flexing, its equal is found only on the YZR factory road racers where it was developed. A slightly modified version of this frame carried Eddie Lawson to his 500cc World Championships and Carlos Lavado to the 250cc World Championship. It makes a level of handling and control possible which has to be experienced to be believed.

For 1989 the FZR 1000 benefits from the next-generation Deltabox. Gone are the dual front down tubes of last year's frame. The engine now bolts directly to the frame at the cylinder head, at the top of the upper case and, like before, at the rear. By making the engine a stressed member (essentially, part of the frame) overall frame rigidity and stiffness are greatly increased.

This increase in frame rigidity translates into improved high-speed cornering performance. And, as the stopwatch so conclusively proves, when a frame is made stiffer, lap times go down. lt also permits a more compact design of the engine/frame combination.

This more compact design makes possible a shorter wheel-base - 10mm shorter, for a wheelbase of only 1 ‚460mm. This shorter wheelbase and 26-degree fork angle improve responsiveness to turning inputs for accurate steering control.

The new frame is complemented by a new Deltabox aluminium swingarm. Featuring a triangulated design for added strength, this new swingarm is strong, light and flex resistant. The results are improved rear wheel control and tracking. Rear wheel maintenance has also been improved with the use of YZF-type chain pullers.

In terms of appearances, both the frame and swingarm have been treated by a special "chemical polish" process for a better-booking finish.

In summation, the frame has undergone a similar transformation to the engine. lt is more compact, stronger and higher performing - the next generation.

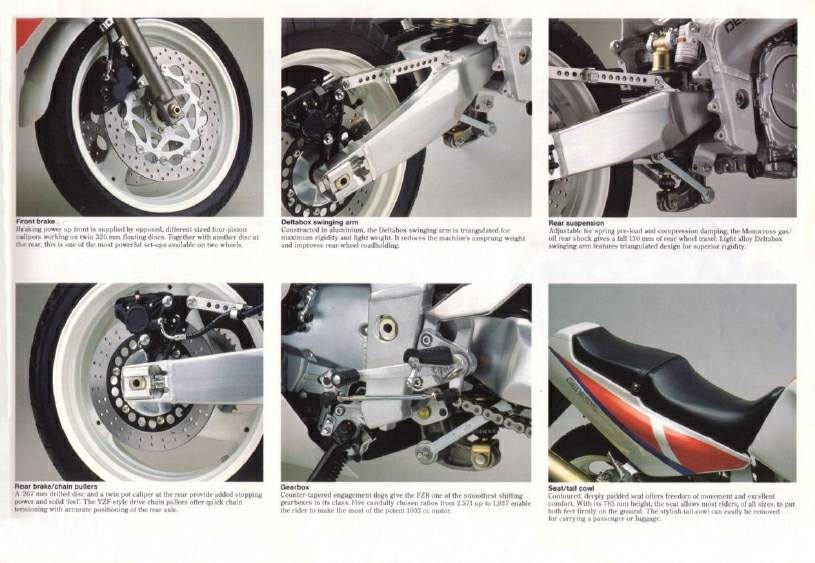

SUSPENSION

To cope with the increased steering loads of the new frame and steering geometry, the front fork has also been strengthened. The stanchions of the telescopic fork have been increased in diameter from 41 mm to 43mm. This greatly reduces their tendency to flex under heavy braking and cornering loads. The result is more precise steering control. The fork is also adjustable for spring preload. Bolting to the stanchions are new aluminium handlebars. These beautifully crafted aluminium extrusions are something found usually only on racing machines.

The rear wheel is controlled by our famous rising-rate Monocross Suspension system. A direct descendent from our factory racers, it delivers progressively stiffer rear wheel damping as the Suspension compresses. For 1989 a modification to the linkage arms increases shock absorber stroke from 50mm to 70mm for improved shock action.

The hydraulic rear shock comes equipped with a separate reservoir for better cooling of the damping fluid and is adjustable for spring preload and damping.

WHEELS AND BRAKES

The most noticeable change in this department for 1989 is the change in rear wheel diameter from 4.50 x 18' to 5.50 x 17". This smaller diameter wheel and the use of very wide, bw profile radial tyres further improves cornering performance. The wheel design - lightweight. hollow-spoke, cast alloy - remains unchanged.

Unlike traditional bias ply tyres which use multi-directional fibres in the tyre casing. radial tyres use uni-directional fibres. This permits flexing of the tread and sidewall, allowing the tread to better conform to and grip the road surface better. Radial tyres also run cooler because uni-directional fibres build up less friction heat than bias-ply tyres when the tyre flexes. And cooler running means longer tyre life.

Dual 320mm front disc brakes feature 4-pot opposed-piston

callipers using pistons of different sizes:

the top piston is larger than the bottom piston (33.96 and 30.23mm,

respectively) for improved "feel". The same 267mm rear disc with dual-pot

opposed-piston calliper is used at the rear wheel. Braking power is even more

reliable, as befits a machine of this calibre.

New for 1989 are larger diameter, hollow wheel axles and swingarm pivot. These axles permit an increase in strength without making them heavier. The front axle diameter has increased from 15 to l7mm, the rear from 17 to 2Omm, and the swingarm pivot from 16 to 2Omm. Both of these features come directly from the YZF racers.

FAIRING, FAI AND ELECTRICALS

The full fairing has also been redesigned for improved

aerodynamic efficiency. The dual headlights are flush with the front cowling,

and the degree of rearward slant of the cowling has been increased. The result

is smoother, more efficient air penetration and a lower coefficient of drag.

The FAI (Fresh Air Intake) system routes cool, fresh air to the airbox via tubes

running from openings at the front of the fairing. This fresh air improves

engine performance because being cooler, it is also denser. Hence, cylinder

filling is improved as more air per volume unit is sucked into the engine. For

1989 the ducts are straight, rather than curved for more direct routing of air.

With the addition of EXUP to the new FZR 1000, the transistor-controlled digital ignition and the control unit for the EXUP are integrated into one unit. This unit not only alters ignition timing in response to changes in mm for maximum performance at all power levels, it controls the amount of EXUP valve opening in the exhaust collector.

Another nice touch is the new electrically operated fuel reserve switch. Like that used on the FJ 1200, it allows the rider to switch over to reserve with a minimum of effort.

The instrument panel has also been redesigned for more compactness. Meter diameters are smaller, and the tach is located higher than the other instruments for quick reading.

And finally, the tail light assembly has also been redesigned for better looks.

SUMMARY

As the FZR 1000 draws ever closer to the YZF factory racers in terms of performance, design and styling, we see a fulfilment of the Genesis concept.

The 1989 FZR 1000 is still very much the FZR 1000, knowledgeable sport riders and racers have come to love. But it is also considerably refined. Lt is faster, better handling and harder accelerating. In short, a balanced performer - balanced on the cutting edge of Sport bike technology.

Bimota YВ6 vs Yamaha FZR 1000

If this machine- 472.5 pounds of exotic materials wrapped around triple-digit horsepower—if this machine had wings it would climb so hard and so high it would give you a nosebleed. Here, Italian sensuality melds with the hardest design reason: Show-quality paint and fiberglass enclose a chassis that argues less is more, that no unneeded part or bracket should ever litter a frame. Weld beads show that smooth, uniform spacing achieved only by masters, and parts everywhere wear machining marks as badges of honor, as the sign they were carved from solid blocks of aircraft-grade aluminum.

It is a Bimota YВ6. It could be yours for only $20,500.

Alongside the Bimota is a motorcycle that shares the same power source: Yamaha's FZR1000. Yamaha's 1988 FZR1000 Genesis engine powers the УВ6; the enhanced version, with an improved cylinder head and a power-valve equipped EXUP exhaust system moves the 1989 Yamaha. The two motorcycles are more than superficially similar: Both use massive twin-beam aluminum frames, and share a sport bike mission. The $7600 Yamaha, though, provides a useful reference point for judging the exotic Bimota.

The YВ6, when first made available a year ago, established Bimota as a leader in motorcycle design, and confirmed the company's newly refound Midas touch. But a hard period came first: Five short years ago, Bimota went bust in a down market no longer able to support the high price of handmade exotica, and the company was forced to rely on Italian legislation to keep its creditors at bay. Today, Bimota's factory in Rimini on Italy's Adriatic coast is flourishing; with 34 employees producing more than 500 motorcycles per year, the company is plowing 25 percent of its profits back into research and development.

Two things contributed to Bimota's resurgence: The overwhelming

success of the Ducati-engined DB1 introduced in 1986, and a deal with Yamaha

Motor Corporation. Yamaha agreed to supply Bimota with its advanced five-valve

FZR750/1000 engines, plus handle distribution of Yamaha-engined Bimotas in the

expanding Japanese market through selected Yamaha dealerships.

In the thriving Japanese economy, Bimota found a market eager for its exotic

creations, and the Italians responded with innovation. Under the de- sign

leadership of Ing, Federico Martini, Bimota produced the FZR750-powered YВ4

racer, its alloy chassis a radical departure from Bimota's previous steel-tube

space frames. The YВ4 promptly won the 1987 Formula One World Championship, and

Bimota followed with the streetable YВ4 and YВ6 in 1988.

This year, Bimota will introduce the FZR400-based YВ7, for which the company has already taken 500 orders from Japan—at $20,500 a pop, the same as the YВ6. Bimota also offers the 750сс YВ4 with fuel injection for $24,800. If that's not rich enough for you, Bimota will happily supply the injected YВ4EIR racer for a cool $45,000.

By comparison the YВ6 is something of a bargain. It shares the same twin-spar aluminum chassis with the YВ4 racer, but uses the 1987/88-model FZR1000 engine—a liquid-cooled, 20-valve four-cylinder with a 45-degree cylinder block, 11.2:1 compression, downdraft induction, and a five-speed gearbox. When Cycle last tested this engine in 1987, it made 122 rear-wheel horsepower at its 11,000-rpm redline, and launched the standard FZR1000 through the quarter-mile in 10.71 seconds at 127 mph. In its YВ6 incarnation, this powerhouse remains stock save Bimota's own 4-into-1 exhaust system.

Our test YВ6, one of only five in the U.S., was bought by Sam Bernstein through the U.S. importer, Philadelphia-based Cosmopolitan Motors. Bernstein, a San Francisco art dealer and founder of the Bimota Owner's Club, U.S. (he also owns a DB1 and an FJ1200-powered YВ5), shares the need for exotic speed with his older brother, Funny Car World Champion Kenny Bernstein. Yamaha supplied the 1989 FZR1000, which has been completely redesigned since last year (see Feb. 1989 issue).

The FZR and YB6, the best and brightest from Italy and Japan, illustrate the similarity of high-performance motorcycling. Surprisingly, it is the Yamaha that gets its design cues from the Bimota. The Japanese have always taken a keen interest in Bimota's design work, and the redesigned FZR 1000 clearly shows the influence of the YВ6.

Tо build a compact machine, Bimota engineer Martini rotated the standard FZR engine back 7 degrees for more vertical cylinder inclination, thus compressing the engine bay and allowing a shorter wheelbase. For its 1989 redesign, Yamaha did fundamentally the same thing to the FZR1000 by tilting its engine back 10 degrees to reduce cylinder angle from 45 to 35 degrees. That change, along with a shorter swing arm, netted a 15mm shorter wheelbase.

Weight distribution is another area of the new FZR that shows a distinct Bimota touch. Martini believes that the Oriental preference for front-end bias is less ideal than a perfect 50/50 front-to-rear weight balance. The YВ6, unladen, has a 49.3/50.7-percent front-to-rear weight distribution. When Yamaha engineers redesigned the FZR, they arrived at a 49.4/50.6-percent distribution—nearly identical to that of the Bimota.

For better handling, the Yamaha also adopted the Bimota's wheel sizes, replacing last year's 17 front/18-rear combination for the more balanced gyroscopic effect of wide 17s front and rear.

Roll the FZR and YВ6 beside each other, however, and it's hard to believe they belong in the same class. Despite its enviable compactness, the FZR feels huge by comparison. That's not surprising: The YВ6 has the physical proportions of a middleweight. Compared to the FZR1000, the YВ6 is an inch shorter between axles, narrower, and lower in the saddle—due partly to its 20mm-thin racing seat. At 472.5 pounds fully gassed, the YВ6 is 50 pounds lighter than the FZR 1000, about average for a 600 sport bike. It's best to think of the YВ6 as a middleweight with one-liter horsepower.

About 10 minutes with the supplied Allen wrenches strip the Bimota bare. Little else but race bikes come apart and go together so easily. The entire fairing is one exquisitely sculpted piece of fiberglass: Loosen the Dzus-type fittings in the lower fairing seam, and the fairing slides right off. The one-piece tank-and-seat section, held by four bolts, lifts off to expose the centrally located plastic fuel tank, and the airbox.

The Yamaha's bodywork comes off in a dozen pieces, making it more time-consuming to remove and less integrated in appearance, but it's also less costly to replace in the event of a tip-over. Bimota's fiberglass panels are beautiful but costly—$3300 for the fairing alone. For the price of a complete set of the Bimota's bodywork, you could almost buy the FZR1000.

Uncovered, the FZR and YВ6 expose strikingly similar frame layouts: Perimeter-style alloy beams wrap around the engines, which are solidly mounted for greater chassis rigidity. Both bikes feature removable subframes—steel for the FZR, aluminum for the Bimota. Here the similarities end.

The Bimota's Verlicchi-made frame resembles Honda's NSR500 Grand Prix frame of two seasons past. Huge, extruded main spars of 3mm thickness connect to a tubular steering head at the front, and massive swing arm mounting plates behind that bear the marks of modern, computer-controlled machining. Intricately machined engine mounts welded to the main spars bolt solidly to the cylinder block. This upper frame section is further supported by a massive cross-member extrusion. In back, the extruded swing arm uses eccentric chain adjusters. Two cross-members, two solid engine-mounts, and the upper shock tower buttress this swing arm pivot area. The frame gives the impression of being extremely rigid and perfectly proportioned, a work of alloy craft that could justifiably share space with the $200,000 jade sculptures in Sam Bernstein's gallery of oriental art.

The FZR's Deltabox frame, in contrast, uses tapered main beams formed from aluminum sheet. This design can put metal and stiffness exactly where they're needed, but requires expensive metal-forming dies difficult to justify for small-scale production. Ditto the FZR's sheet-formed swing arm, an expensive, 10-piece affair with sliding-block chain adjusters.

Japanese sport bikes rarely look appealing with the bodywork removed, and the FZR1000 is no exception. The requirements of mass production prompt the use of injection-molded ABS plastic panels to cover what is too time-consuming and expensive to finish. Hoses and wires run amuck on the Yamaha chassis. Weld beads laid down by Japanese robots can't hold a candle to the flawless hand welds of Italian craftsmen.

Now look at the YВ6, and see Michelangelo-quality detail finish. All hydraulic lines are braided steel. Every piece is meticulously machined, perfectly fitted. All the electrical components are concentrated around the battery, leaving the rest of the frame uncluttered. One part suffices where two might have been fitted. Bimota design leaves no excess material, no rough edges.

Even small pieces, such as the pipe hanger bracket, are hollowed, thinned for lightness. You see such effort on pure racing machines where the cost of shaving a few grams of weight is rewarded at the finish line. This is the difference between mass production and the handwork of artisans, and that difference makes it easy to understand why the Bimota costs what it does.

Pared to the bone, the YВ6 has the dense mechanical simplicity of a racer, backed by front-line chassis components. Three-spoke Oscar wheels—a 3.5-by-17inch front, and a wide, 5.5-by17-inch rear—mount European-spec Michelin A59Х and M59Х radials: a 1301 60 front, and a massive 180/60 rear. A pair of four-piston Brembo calipers puts the squeeze on 320mm floating front discs. A smaller, 230mm rotor resides in back.

Suspension quality matches that of Bimota's real racers: a 41.7mm Marzocchi fork with adjustable anti-dive in the left leg, a rebound damping adjuster in the right, and air caps—though Bimota specifies atmospheric pressure. In back, a single, remote-reservoir Marzocchi shock offers 12-position compression and 25-position rebound damping adjustment, and a threaded preload collar. Unfortunately, only the rebound adjuster is accessible with the shock in place. Such is the price of the YВ6's dense packaging.

The FZR is similarly equipped—same basic brake design, though manufactured by Nissin, and same wheel sizes wrapped in Pirelli's МР7 Sport radials. The Yamaha's massive 43mm fork offers preload adjustment only, but the gas-charged rear damper also incorporates a four-position rebound damping adjuster.

Both chassis offer ride-height adjusters in the single-shock rear suspensions—a genuine racing touch. The Bimota goes the Yamaha one better with eccentric steering-head cones that can alter rake from 23.5 to 26.5 degrees, with 25 degrees, 4.03-inches of trail as standard. The longer, heavier FZR steers through slightly slower geometry: 26 degrees and 4.2 inches.

As the chassis numbers indicate, the FZR 1000 feels ponderous at low speeds, especially in company with the feathery YВ6. On the other hand, the Yamaha's more compliant suspension provides supple relief from the constant pounding delivered by our YB6's rear shock, which was not working to specification. A severe shortage of rebound damping allowed the shock to top-out hard over rough pavement, and a broken adjuster prevented us from cranking in more damping. The potholed streets of San Francisco were especially hard on the Bimota, rattling the bodywork, jiggling the rubber-mounted Yamaha instrument cluster. We headed for smoother macadam, where even a rubbery rear shock could not spoil the magic of the YB6.

On the mythical mountain roads of Mann County, the FZR1000 traded its supple ride for more chassis movement under braking and acceleration than the YВ6. Off-throttle cornering loads the FZR's front end, and the bike shows a slight tendency to stand up under braking. The FZR is happiest when braked upright, then flicked into the turn in modern GP fashion. Ridden this way, the Yamaha instantly builds speed more appropriate for the racetrack than for the street.

The Bimota's firm suspension and anti-dive fork provide a more consistent chassis attitude. Steering is absolutely dead neutral on the brakes or on the gas. It's important to remember here that high corner-speed depends to a large extent on the rider's trust of the front end. How much he trusts it determines how hard he is willing to push it. You instinctively trust the Bimota's front end. No matter how deep you brake, or how hard you flick the bike into corners, the front end never feels like it's going away.

Ridden quickly on a smooth road, the Bimota has an almost magical ability to disappear beneath you, leaving only the road to deal with. The combination of lightness, unshakable stability, and tack-sharp steering makes the Bimota easy to ride fast or slow, on sweepers or switchbacks. On tight roads, the heavier, longer, slower-steering FZR takes more effort at the handlebars, augmented by body English, to initiate a quick turn. FZR and YВ6 brakes are equally powerful—like hitting a brick wall—though the Bimota's hard-compound pads require more effort at the lever. Both bikes offer more corner clearance than sane people need on the street. The Yamaha's Pirelli tires are the best standard-issue rubber we've ever sampled, the Bimota's Michelins merely excellent.

Prudence prevented us from thrashing Bernstein's Bimota at the dyno and drag strip, but side-by-side acceleration contests had the Bimota shrinking in the FZR's mirrors. That's not surprising: Our YВ6 ran decidedly flat in the middle and upper rev ranges. The '89 FZR1000 EXUP engine—which shows a whopping 14-horsepower spike from 6000 to 6500 rpm—offers crisp, immediate throttle response.

The pilot-production '89 FZR1000 we tested in February 1989, was a powerhouse-114.9 rear-wheel horsepower—that posted a quarter mile best of 10.8 seconds at 129 mph. Our 1989 production FZR1000 fulfilled the promise of the pilot bike, pumping out 113.9 horse- power and scorching the drag strip in 10.8 seconds at 128 mph. The production FZR, however, proved slower in 45to-70-mph roll-on acceleration than the pilot bike, giving the low-speed advantage to the YВ6.

The Bimota leaps to an early lead over the FZR at low revs, where its combination of lighter weight and crisp low-speed jetting (and despite slightly taller gearing) keep the Bimota ahead until the engine goes flat at 5500 rpm—abeds that it constantly poses the question: Are you good enough as a rider to appreciate this?

But you don't have to ride the Bimota well—or ride it at all, for that matter—to know what makes it worth the money. In an age of mass-produced sameness, the YВ6 is a machine of inspiration, ingenious design, and flawless beauty, the object of obsessive attention to detail by artisans who love motorcycles.

You could ride the Bimota fast all day without ever spinning the engine higher, but that's a bit like breaking into Fort Knox and taking just enough for lunch. Better to sharpen the YB6's jetting, and use it all.

We're talking about a clash of cutting edges here. Both the FZR and YВ6 have speed capabilities that cannot be fully explored on the street. Neither bike is remotely practical, though the Bimota's firm suspension, wafer-thin solo seat, clip-on bars and radically rearset footpegs make the FZR feel like a sport tourer by comparison.

The FZR1000 is the fastest, best handling big-bore street bike ever made in Japan. But the Bimota's sharp handling, light weight, and magical combination of agility and absolute solidity place it closer to sporting perfection than any large-caliber motorcycle we have ever ridden.

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |