Kawasaki ZX750E1 vs. Yamaha XJ650LJ

In life we’re faced with choices: republican or democrat, blond or brunette, paper or plastic? Shopping for a new motorcycle in the early 1980s, you also had to choose between normally aspirated or turbo models.

As the 1980s picked up steam, each of Japan’s Big Four (Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha) offered up at least one turbocharged model based on a standard offering. The train of thought was simple: Combine a 650cc or 750cc engine with the power boost of a turbo and wham! — big power. For some shoppers, just the allure of turbo technology was reason enough to buy. And while each manufacturer (excepting Honda) used the same basic formula (inline-four engine + turbo = new model), each company’s creation was a bit different.

To get an idea of what the Turbo Wars netted, we pitted Kawasaki’s ZX750E1 (also commonly referred to as the GPz Turbo) against Yamaha’s XJ650LJ Seca. Kawasaki had delivered — albeit unofficially — the Z1-RTC in the latter part of the 1970s, but the ZX750 turbo was a true production unit and therefore better suited for this standoff. Both of the chosen combatants were based on existing offerings, but in keeping with their higher output mills were better dressed and equipped.

Getting to know them

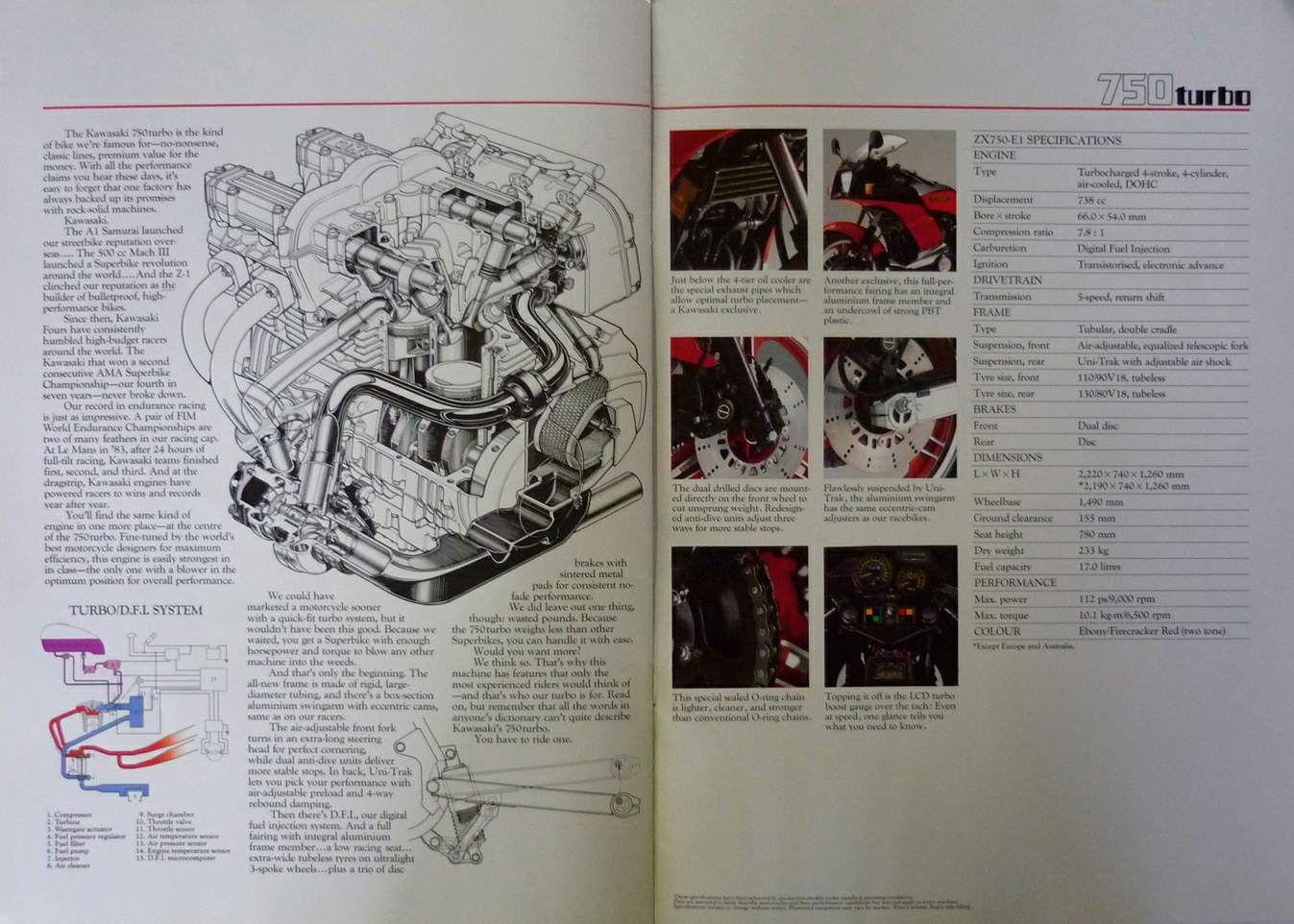

Following the debut of the original Z-1 in 1973, Kawasaki positioned itself as a dominant player in the high-performance market. Engines from the Z and later KZ models routinely found their way into championship-winning drag bikes and were widely considered to be among the strongest mills available. With other manufacturers exploring turbo power, adding a turbocharger was a logical step and created a new high-horse monster for Kawasaki.

Yamaha’s history was not carved from the same stone as Kawasaki’s, but the company had a number of diverse machines to its credit. Yamaha’s legendary 2-strokes and the XS650 twin and XS1100 inline-four earned high honors among riders on the street, and Kenny Roberts took the Yamaha banner to the winner’s circle repeatedly during the 1970s.

On paper, the ZX and XJ share a number of similar traits. Beneath their futuristic body panels they both have a tubular steel chassis carrying an inline-four engine. The similarities continue: The ZX wheelbase is 58.7 inches; the XJ measures 57.1 inches. Full of fuel and fluids the ZX weighs 556 pounds; the XJ 567 pounds. Seat heights are almost identical, falling within 0.3 inches of each other with 30.7 inches for the ZX and 31 inches for the XJ.

But even in their commonality, they are very different machines. The ZX mill displaces 738cc; the XJ 653cc. That difference in displacement gives the Kawasaki a 10hp edge over the Yamaha, with a claimed 95hp at 9,000rpm. This bump in power shows up at the drag strip, with the ZX trumping the XJ by more than a second in the quarter mile at just over 11 seconds against the XJ’s 12.68-second time.